Constructive Conflict Guide - Part 4A: De-Escalating Destructive Us-Versus-Them Confrontations

by Heidi Burgess and Guy Burgess

October, 2021

Introduction

This section combines responses to two different, but highly inter-related, problems. The first is the tendency to oversimplify complex intractable conflicts to simple "us-versus-them," "good guys-versus-bad guys" narratives. Almost all difficult conflicts are more complex than that, with many different issues, interests and needs, "good guys" and "bad guys" on all sides, and helpful and harmful actions being taken by all sides as well.1

The second problem is escalation, which we have long asserted is "the most destructive force on the planet," because it causes people to do all sorts of terrible things that they would ordinarily not consider doing (including, at the extreme, genocidal violence and, potentially, nuclear war). "The enemy is not the other side," we tell our students and anyone else who will listen; "it is conflict escalation."

This section first examines what causes these two problems and what their effects are. We then look at a long list of things that we and others can do to start addressing these problems successfully.

Us-Versus-Them Over-simplification

Let's discuss oversimplification first. Most intractable conflicts are very complex. But people, by nature, tend to have trouble dealing with and, therefore, dislike complexity. They try to simplify complex stories into something they can more easily understand and categorize—some things are "good," others are "bad." New information that corresponds to the narratives that they already believe are "accurate." Information that contradicts what they already believe is "wrong." People trust themselves more than they trust others, and when there is a question of who is right and who is wrong, or who is good and who is bad, most people will automatically put themselves and people like them on the "good side," while they will put people who are different from them (and especially those who are opposed to things they want or believe) on the "bad" side.

These very different world views then drive the sense that the other side in a conflict is "bad:" "selfish," "self-serving," "hateful," or even "evil." We tend to assume that it is their choices and their behavior, that is causing our own problems, not our own choices and our behavior. Not only is that false (on both sides), but such over-simplification is problematic for other reasons.

First, it tends to spiral. If we blame "them" for everything that goes wrong, they will likewise respond by blaming "us." If we lash out about that, they will lash back—sometimes escalating the rhetoric, perhaps even adding in a negative behavior.

These tit-for-tat exchanges can continue, sometimes escalating to full-blown violence, even war. Although "war" is not something we tended to worry about in the United States, at least until recently, there are some prominent people who are publicly suggesting that "civil war is inevitable," or that it is already happening. Even short of war, the protests we saw in the United States in the summer of 2020 and then again on January 6, 2021 suggest that a return to large-scale violence such as we last saw in the 1960s and 70s is certainly possible.

Another problem with such over-simplification is that it assumes that the solution to "the problem," whatever the problem is, is to just "get rid of" the other side, or subdue them, over power them, or, perhaps, convince them that they are wrong and you are right. None of those approaches is likely to be possible, or to work, because the other side thinks the same way. So the situation is like an equally-matched tug-of-war. But unlike tug-of-war, in which one side eventually prevails, and the game is over, the other side in these contests gets up, dusts themselves off, and comes right back to the fight. So the fight goes on and on, often getting worse, not better, for all sides.

Avoiding and Reversing Over-Simplification

Like many problems, over-simplification is most easily "solved" by not doing it in the first place. But that's hard to do--everyone oversimplifies all the time out of necessity. We can't possibly take in, store, and understand every bit of information that comes our way. But if we are aware of the dangers of over-simplification, and we are aware that conflict narratives that say that "the problem is the other sides' fault" are almost always wrong, that's a good start.

Rather than going along with that narrative, and the related notion that everything would be fine if "they" either understood the truth, came around to our point of view, were resoundingly defeated, or simply disappeared, and working toward that, it is important to find out what is really going on and then base our response on that more complex, nuanced understanding of the problem.

In almost all cases, "they" are not going to do any of the things the simple-narrative people hope for (such as changing their minds or disappearing), as they think exactly the same way about you. Most often also, all sides are in some way contributing to the problem, by doing things that unnecessarily make the other side angry or afraid and hence drive the escalation spiral. So a second step, after rejecting the simple "it's their fault" narrative, is to examine if and how things you or your group are doing may be contributing to the problem. An example is the campaign to "defund the police" when complete elimination of the police, most often, was not what was being suggested. The language, in that case, was unnecessarily alarming, and just created enemies among people who might have been allies in the broader campaign for police reform and accountability.

How should we get this more complex, nuanced view of the problem? We need to learn more about the other side--not about how bad they are, but why they believe what they believe, why they respond to us the way they do, and why they advocate for the things we think are so awful. Most often people who look to be stupid or evil actually have good reasons for thinking and acting as they do. If we understand those reasons, we will be in a much stronger position to work with them to try to solve our many mutual problems.

Learn Why The Other Side Thinks and Acts The Way They Do

So how do we do this? For a start, we need to start reading, watching and listening to things the other side reads, watches, and listens to. That will help us understand where they are getting their ideas, and what they are basing their attitudes and behaviors on.

You do not necessarily need to read/watch/listen to the most extreme spokespeople on the other side, as that will likely make you mad and convince you that they really are as bad as you thought. BUT, it will give you an insight into why others who listen/read/watch to those people come to the conclusions that they do. Listening to Donald Trump, when he was President, infuriated me. But it also showed me why so many people believed what he had to say, and it gave me a sense of the issues that they were concerned about.

Equally or more valuable, however, is reading/watching/ listening to moderates on the other side. These people are much more likely to explain the legitimate concerns, fears, interests, and needs of people who differ politically from you. They will explain what your side is doing to make them angry or fearful, and what you can do, perhaps, to improve relationships with them and people like them.

While you can say (or think) that you don't want to improve relationships with people like "them," if we don't, our polarization and escalation is just going to get worse, and we are not going to get anywhere on solving any of our pressing problems. It has long ago been proven that politics is a back-and-forth proposition. One side wins, then the other side wins. In the United States, and in many other places, the power of the two sides is approximately equal, so neither side can successfully impose its will on the other. The alternative to cooperation is political stalemate and dysfunction, most likely accompanied by increasingly dangerous hyperpolarization and escalation.

Take, for example, the conflict over race and racism, particularly as it is being played out in current "diversity, equity, and inclusion" programs. The Progressive Left sees these programs as the key to abolishing systemic racism. Since the overwhelmingly White meritocracy has ruled for so long, and racial minorities have been downtrodden in so many realms (education, jobs, housing, income, wealth, health, etc.), Progressives assert that the way to remedy this is to get Whites to understand that they have been unfairly "privileged" and empowered for far too long, and it is now time for them to actively remedy that by stepping aside and letting people of color lead. "Diversity" to Progressives means more people of color and fewer and less influential Whites.

However, Progressives' definition of "diversity" most often does not pertain to ideas and sociocultural values. While "diversity" at predominantly liberal universities means inclusion of non-Whites (as well as those marginalized because of gender-identity), it does not mean inclusion of those with more conservative, traditional, and largely Christian values. This is why we are hearing so many stories of people being "canceled" for failing to toe the Progressive line on race.

Ibram X. Kendi asserts, there is no such thing as being "not racist." Whites, he says, are either racists or "anti-racists." That means anyone who doesn't take a stand, who doesn't actively work against racism in the ways that Progressives demand, is a racist (in other words, "evil.") In addition, Kendi and other "anti-racists" assert, those who advocate for treating each person as an individual, not as a representative of their race is, by his definition, a racist. They reject the notion that a person's value derives from their accomplishments (a measure tainted by the tilted playing field), and characteristic of the maligned "meritocracy." Virtue is determined solely by race. So whites should be shamed and held back for their "privilege," giving the formerly oppressed the opportunity to catch up, or even move ahead. Other class-based measures of relative advantage and disadvantage are considered irrelevant, as is the extent to which a person worked hard, or otherwise contributed to society.

John Burton and other human needs theorists in the conflict resolution field long ago explained, very persuasively in my view, that deep-rooted conflicts are largely caused by perceived threats to an individual's ability to meet their fundamental human needs, most importantly to assure their security, identity, and recognition. It is not hard to see how the Progressive view might be seen as a threat to the ability of Conservative Whites to meet all three of these needs.

The notion that one should be ashamed of their race and their socio-cultural heritage because they are "privileged" is a slam on a person's fundamental identity. Liberals used to argue that it was unfair to demonize someone for an attribute they were born with--their race. But now it is okay to do that to Whites to "get even." But many whites don't feel any better about that now than Blacks did way back when (and still do when it happens). It is an affront to one's identity either way.

Also, when people get fired for speaking their minds, when they get denied a good education because their ancestors were "privileged," (as happens when whites are denied college entrance because of their race, or advanced classes are cancelled in elementary or high schools because they tended to be disproportionately White), this is an attack on Whites security, as it threatens their ability to get or keep a good job, and to have a secure livelihood.

And lastly, "recognition" is the need to have others recognize your needs and empathize with you. In Kendi's antiracism movement, Blacks and other people of color should be recognized, but Whites should not. But recognition, along with identity and security, are fundamental needs to Whites as they are to Blacks.

When the ability of people to meet their fundamental human needs are attacked, Burton argued, people will fight back hard. They will continue to fight until they feel secure, until they feel that their identities are valued and they are fairly recognized for who they are and what they do or have done.

If Progressives would read, watch, and/or listen to some of the Conservative responses to diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, they would better understand why conservatives oppose them and why they are most likely to fight long and hard against them and the ideas that are being taught in them.

Wouldn't it be better to go back to an anti-racism approach more akin to Martin Luther King's which, like Gandhi's, acknowledged the humanity, the value, and even the "truth" of the other, and sought to work with them, rather than against them for a future everyone would want to live in? And, if this moral appeal is not enough, it is looking increasingly likely that the anti-White agenda will lead to electoral defeat and, quite possibly, a second Trump presidency.

Note: The above comments are offered from the perspective of someone who has spent her entire career trying to help people escape the destructive spiral of runway conflict, not as an advocate for a particular side. My goal is to figure out how we can bring people in the U.S. and other deeply-divided societies together in ways that repair increasingly dysfunctional democracies, resist authoritarian tendencies, and prevent large-scale civil unrest. When the power of both sides is roughly equal, power-over strategies simply do not work. They just lead to continued polarization, escalation, and eventual catastrophe. I am trying to help advocates on both sides to understand this before we jump off the metaphorical cliff. We all need to switch to a power-with strategy to begin to work together to solve our mutual problems, true racism being one of them, unbridled escalation being another.

Conflict Mapping to "See" Complexity

When I teach my graduate course on Intractable Conflict, the main semester activity is learning how to draw conflict maps, which are excellent ways to depict complex systems, and the many interacting factors that are almost always present in intractable conflicts. This is a pretty involved process if it is done carefully, but it can also be done fairly quickly and easily if you get a few people together to unpack a thorny problem. All you need is a big piece of paper or a white board (We tell our students to go out and get a roll of brown wrapping paper if they don't have a white board available), post-it notes, pens, and markers. Then you set to work mapping the conflict of your concern.

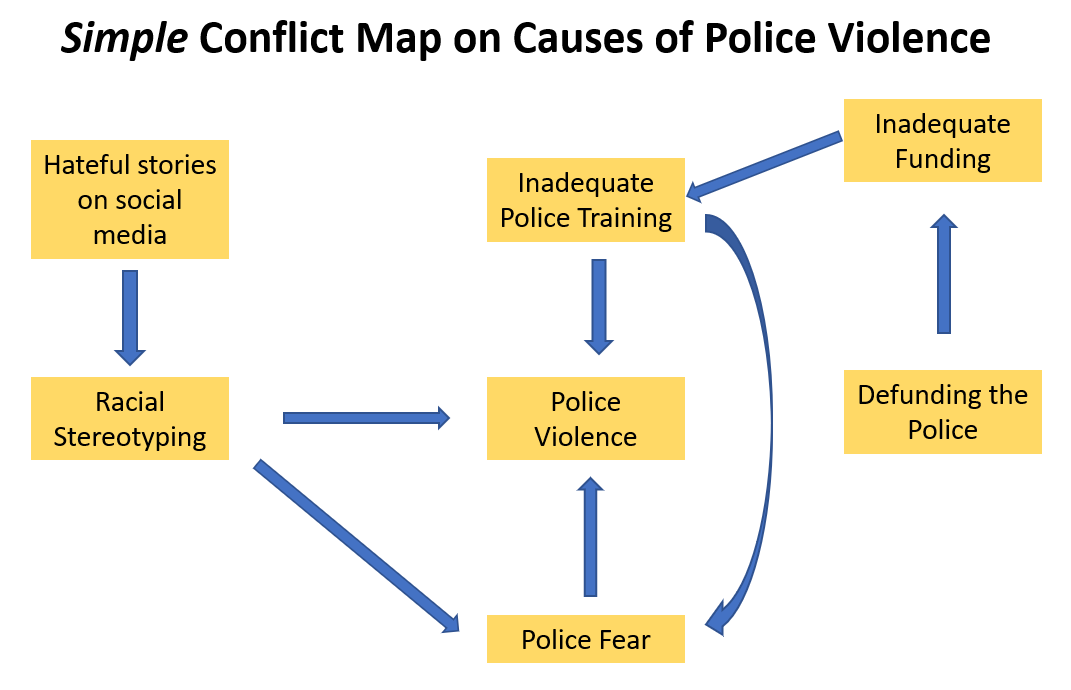

For illustration, let's consider the conflict over police violence in the U.S. Put a post-it note in the center of the big piece of paper or white board and on it write "police violence." Then ask yourself and your co-mappers, what factors contribute to police violence? "Racial stereotyping" might be one answer. Write that on a post it note, put it to the left of the center note and put an arrow between them, with the point going toward police violence.

What else contributes to the problem? "Inadequate police training" might be another answer. Put that on a note and put an arrow toward the center. "Police fear" might be a third. Put an arrow going from police fear to police violence, but also, perhaps, from stereotyping to fear because stereotyping of blacks as violent likely increases police's fear of blacks in their encounters with them. Inadequate training might also lead to fear. Put in another arrow. What leads to stereotyping? Hateful stories on social media might be one answer. Put that on the map. What leads to inadequate police training? Inadequate funding might be one answer. Ah-ha! That suggests that defunding the police might contribute to police violence, not deter it.

Keep going like this until you have listed all the factors that you can think of that might lead to police violence, the things that lead to those things, and, if you have time and space, the things that lead to those things. Then start putting in arrows showing the interrelationships between these factors.

You can already see, this isn't a simple "us versus them" problem. The more you understand what is creating the problem, the more you will be able to see what might be done to try to fix it. And you might see that policies you are advocating, such as "defunding the police," might be counterproductive. This is what is meant by the phrase "complicate the narrative" a phrase coined by Amanda Ripley, a journalist who is leading the way in the United States towards more constructive journalism.

Complex Versus Complicated Systems

Another aspect of avoiding over-simplification is understanding the nature of complex systems, which characterize most intractable conflicts. Most people understand complex to mean "complicated" or "hard to understand." They are hard to understand, but systems theorists (and a growing number of conflict theorists) make an important distinction between "complex," and "complicated."

Complicated systems have many parts, but the parts are connected in determined, predictable ways. Cars are complicated, computers and cell phones are complicated. But they were designed by people, who understand how they work, how the parts work, and how the parts are connected. When a part breaks, they can find it, fix it, and make the machine work again. In addition, in complicated systems, the relationship between inputs and outputs is determined and linear. This means small inputs will create small, determined outputs, and large inputs will create large determined outputs. So when you push gently on the accelerator in a car, the car will move forward slowly. If you floor it, the car will speed ahead as fast as it is able. How much the car speeds with different levels of pressure on the accelerator is predictable, at least if one is driving on flat ground.

Complex systems have many interconnected parts, but they are not connected in known or determined or linear ways. Rather, they are adaptive--each element in the system responds (adapts) to its environment in a (sometimes) predictable way. But the system, as a whole, is not determined or predictable--it can produce novel and unexpected outcomes. That means the behavior of the whole cannot be explained by the behavior of the parts, and you cannot fix complex adaptive systems by taking out the broken piece, fixing it, and putting it back in its place. It won't work the same way it did before. You have to be much more experimental when you try to intervene in complex adaptive systems--trying something, watching the effects, adapting, and trying again.

As Wendell Jones points out in his BI essay on Complex Adaptive Systems, each human, in an of themselves, is a complex adaptive system.

The human brain is the most complex system known to us, in the universe, with one hundred billion (1011) neurons and ten thousand trillion (1016) connections (synapses) among those neurons. At each of these synapses, complex interactions occur among electrical charges and over 100 chemicals. Much work is currently under way to examine aspects of the emergent property of the brain that we know of as consciousness. From the earlier discussion, one can see that an individual's actions might be generally predictable, but those actions can never be precisely predictable. In addition, our human self-awareness (an emergent characteristic) generally allows us to choose how we interact with one another or a group.

So we can't predict how, exactly, any human will respond when presented with a particular situation. And when you get many humans interacting with each other, the situation becomes even less predictable. That means that we can't "fix" complex adaptive systems as if they were simple or even complicated systems. There are not cause-and-effect relationships, where a broken piece can be replaced and the system will work again. Outcomes aren't linear. We might push hard in one place and nothing will happen. Push a little elsewhere, and the entire system will rearrange itself.

Jones went on to explain:

The attribute of complex systems that provides direction for intervention is the nonlinear self-organizing property. In these systems, whether a jazz ensemble or an ant colony, agents in the system adjust to every stimulus in ways that are not linear. That is, small input changes can produce large output changes. This is actually very encouraging, for it suggests that small inputs into a protracted or intractable conflict can conceivably produce large effects.

People working the field of dispute resolution need to be willing to embark on "enlightened experiments." That is to say, change something and work with the system while it adjusts to the change. If a positive result is not immediately apparent, wait awhile. It may yet be coming. Many times, these initial changes will not produce a significant reorganization of the system, but there can be changes that will result in reorganization within the system that will be beneficial. Such "enlightened experiments" could include altering aspects of the negotiations, such as changing the venue, changing the negotiation teams, adding culture-specific features to the negotiation, etc. Although it is impossible to tell which change will make the biggest difference, small changes in complex adaptive systems can lead to significant changes and potential negotiation breakthroughs.

In summary, making a difference in the midst of intractable conflict will not come from a reductionistic analysis of the system, conducted in hopes of designing and deploying a "definitive" intervention. Instead, evolutionary progress toward resolution can be possible through mindful experiments from within the conflict and then moving with the self-organization that follows.

The impossibility of predicting and controlling conflict need not result in a sense of hopelessness or resignation. It can, instead, propel us to a deeper exploration of the nature of complex adaptive systems and the amazing possibilities that reside within such self-organizing systems for constructive change.

Bottom Line

So, bottom line, we need to see the conflicts we care about not as simple "us-versus-them", "good-guys-versus-bad-guys" situations, but rather as what they are--complex adaptive systems. Once we see that, we can learn as much as we can about how the system is "put together," and how it works, and then we can begin to experiment with inputs we can make into the system in the hopes of changing it in the way we would wish. If an input doesn't seem to work, wait awhile. Watch. It may bring about the desired change, just more slowly than we expect. Or it might not--it might actually lead to further problems. If so, figure out what went wrong, and try something else. Success is by no means certain, but it is much more probable if we understand the nature of the problem we are dealing with and respond accordingly, rather than simply continuing to escalate an escalated conflict further and try to "win" an unwinnable game.

Escalation

It is easy to see how this over simplification leads to escalation, but many other factors do too. This diagram shows many of them.

Beginning at the Lower Left

- We have initial, competing "in-group/out-group" identities, which often provide the foundation for the us-versus-them over-simplification we talked about above.

- This differentiation between groups causes people to avoid people in the out-group. Instead, they try to work with, live with, and talk to only "their own," and not the other group as much as possible.

- Communication between groups thus gets increasingly strained, until it is cut off altogether. The only information each group gets about the other is filtered by the media—and as we will discuss in the communication section, each side seeks out and only pays attention to biased views of "the other."

- That leads "us" to see "them" in the worst possible light (worst-case bias).

- We also tend to see ourselves as the victims of "their" bad actions, (sense of victimhood),

- Causing us to have mounting grievances against "them."

- We also increasingly distrust "them" and assume that anything that they say is insincere and deceptive.

Enmity Reinforcement

- All of this feeds back upon itself strengthening the divisions even further.

- People begin to engage in what we call "recreational complaining"—the tendency we all have to enjoy sitting around (physically together or on social media) complaining about "the other." It feels good to show how bad they are, to reinforce how good we are—and to do so among as many like-minded people as possible, as that reassures us, again and again, that we are righteous.

- Each side comes to think of the other side as fundamentally evil, possibly less than human, and therefore it's okay to treat them very, very badly, because they're not worthy of respect or humane treatment.

- But this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the more we complain (and act out against them), the more we are validating their sense of victimhood and their grievances against us. So then they complain and act out against us, so that proves they are even worse than we thought!

- This cycle of tit-for-tat responses increase our anger and fear and contribute to a growing sense of urgency. We need to act now to subdue them, or else terrible things will happen! (Ironically, this is an urgent situation that needs quick action—not against them, but against escalation! But people caught up in these dynamics seldom see it this way.)

Tactical Choices

- This deep enmity influences our tactical choices.

- We don't consider any of their interests or concerns as legitimate, so we make no effort to meet them.

- We assume all the issues in dispute are zero-sum, in other words, the more they get, the less we get. So we approach every issue competitively and coercively. We see cooperation and compromise as signs of weakness and out of the question.

- We escalate the nature of our responses to them. We start getting increasingly hostile, more coercive, stronger in our demands, and our tactics. And of course, so do they.

- To strengthen our side, we try to build coalitions, pulling more and more people and more and more organizations to our side. And we force people to take a side, because both sides are doing this. So standing in the center gets less and less feasible. If you're not with us, you're against us. You have to take a side.

- The "quid pro quo" that accompanies coalition formation tends to draw us into other people's conflicts regarding other issues. This locks everybody into a never-ending web of conflicts (since it's virtually impossible to resolve them all at the same time and relieve oneself of one's obligations to coalition members).

- This process affects both leaders and followers. Leaders feel a need to be "strong," which means they need to take ever-stronger positions against "the enemy," increasingly refusing to cooperate with them or even talk to them. Advocates of moderation or compromise become increasingly discredited and marginalized.

- The "cautious shift," takes hold where, especially in crisis situations with uncertain information and distrust of the other side, there is a strong tendency to "play it safe," and not make concessions that could help de-escalate the situation.

- Reluctance to make concessions can also result from the fear of being double-crossed, which is particularly likely when the "other" is distrusted.

- Leaders and the media "play to their base" by falsifying information to tell people what they want to hear. (More on this is in the communication section.)

- There's also a tendency to see yourself as invincible. "We're right, they're wrong," and "we're going to win. Just keep on escalating the conflict and they'll back down, or we'll win decisively in the next election."

Falling into Traps

- All of these choices get us into a set of traps that act like ratchets—once you pass a certain point, it gets extremely hard to back down. One of these is what we call “the sacrifice trap.” The thinking goes, “we've put this much effort in, we've expended so many resources, so many people have been hurt, we can't possibly give up now, it would be a waste!”

- And we don't want to admit that we were wrong, which is what we call “the shame trap.” So we keep on pursuing our losing course of action because we can't admit we made a mistake.

- The "personalization break-over” is another trap we fall into. When one is dealing with interpersonal conflicts, it's personal right away. But when one is dealing with intergroup conflicts, or national conflicts, it may not become personal until somebody in your family or your close associates or you personally are hurt. That ratchets the escalation up even further. You think much less about what you're doing, and just lash back. This is where the focus shifts sharply toward interpersonal hatred and away from substantive issues.

- There's another ratchet when conflicts turn violent. Violence creates a strong desire for revenge and self-defense, and this just keeps escalation intensifying even more.

And the Conflict Continues to Grow...

- As all this is going on, the size of the conflict continues to grow.

- There get to be more issues in contention, more resources expended, more people involved.

- This makes it harder and harder to turn back, reinforcing the "sacrifice trap."

- Eventually, you get to the point as early conflict theorists Pruitt and Rubin pointed out, one's goals change from doing well (at the very beginning) to winning (at the middle) to hurting the other, even if it hurts yourself as well.

All of the circular arrows on this diagram are intended to show that all of these behaviors are positive feedback loops, reinforcing each other, making each stronger, happening more often, and intensifying the conflict increasingly over time.

Is there any question why we might want to avoid this process?

The good news is that there is a lot that we can do to slow and ultimately reverse the processes of escalation. Once we understand the many ways in which escalation can trap us, we can avoid those traps. If we discover that we have already fallen into a trap, we can work to climb out. In addition, there are many things we can do to help our communities resist destructive escalation while, at the same time, more constructively addressing important issues that are at the core of most conflicts. The same is true with the "trap" of over-simplification.

In the materials that follow, we will look at ways to overcome and/or dismantle both problems, often simultaneously.

Reversing Over-simplification and Escalation

As is true with many problems, it is much easier to avoid these issues in the first place, than it is reversing them once they have really taken hold. However, when we are talking about "intractable conflicts," these two problems most likely are strongly embedded in the conflict system already. So it is necessary to reverse these dynamics, or, at the very least, prevent them from getting worse.

The interlocking nature of the problems of over-simplification, escalation, and polarization means that they can usually be addressed simultaneously using the same set of strategies. These include the following.

Escalation Awareness

The first critical step toward de-escalating conflicts is building awareness among disputants about how very insidious and dangerous unbridled escalation is. When people are drawn into its downward spiral, they do not understand that their images of the other side are distorted. They do not understand that their own actions are likely contributing to the problem and making the other side respond as it is doing. If disputants can be shown how their own actions are driving the other side to respond as they are; if they can come to realize that at least most of the people on the other side are not as bad as they think (that's not including the bad faith actors, who maybe are that bad), they (good-faith actors) are more likely to be willing to change their own behavior once they realize that they are making escalation and polarization worse.

Tactical Escalation

Sometimes disputants (particularly low-power disputants) try to escalate a conflict intentionally because the other side does not care about an issue as much as the lower-power party does, and the lower power party thinks that by escalating the conflict they can get the other side's attention, or even get them to agree to make desired changes. Sometimes this is true, and it works, as Louis Kriesberg explains in his essay entitled Constructive Escalation.

But this is a dangerous tactic, not only because escalation can quickly get out of control (as we discussed above), but also because it has a tendency to strengthen one's enemies as well as one's friends. So, for example, the Left held huge marches around the world in the summer of 2020, protesting the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This drew a great deal of attention to the problem of police violence, which was good. However, in addition to almost universally-supported calls for strong and effective measures to prevent and punish police misconduct, there were also widespread calls to "defund the police." This implied to many that the advocates of this policy believed that all policing was oppressive or otherwise harmful, and should be eliminated entirely. However, it turns out, most U.S. Blacks, who are victims of widespread community violence, generally are against defunding the police. Rather, they want the police in their neighborhoods because they feel that police are doing more to prevent crime than to cause it. So not much defunding of police has happened and where it did happen, the funds were soon restored.

But, the campaign has been a huge rallying cry for the Right, which has been able to successfully use it to paint Democrats as "anti-police" and "pro-crime." William Saletan writing in Slate asserts that argument was a key reason that the Democrats lost many Senate seats in November of 2020. So in that case, escalation worked to strengthen the opposite side more than it worked to strengthen the party that was demonstrating.

For these reasons, tactical escalation efforts designed to promote awareness of a problem and efforts to solve it should be undertaken very carefully, and only if it is deemed the only way to gain the attention of the other side and the larger community. Parties using tactical escalation should also engage in other de-escalating behaviors and language simultaneously, so as to give the other side an opportunity to respond collaboratively, instead of hostilely. Ways of doing this are suggested below.

Constructive Confrontation

One alternative to intentional conflict escalation is what we call "constructive confrontation." This is a much more complex process that has four steps. First is carefully assessing or mapping the conflict to enable you to "see the complexity" and understand, as much as possible, what is really going on. Second is setting your goals. Rather than seeking total victory, which is likely to be a recipe for continued destructive conflict, conflicts can be de-escalated by setting goals that allow the other side to meet as many of their interests and needs as possible too. A closely-linked step is developing an image of the future. If you can develop an image of the future in which everyone would want to live, that is going to be much more successful than seeking an outcome that is completely unacceptable to the other side. The fourth step in constructive confrontation is considering response options which can be interest-based (focused on the negotiation of mutual interests), needs based (focusing on meeting unmet human needs through problem-solving workshops and related processes), or rights based (focused on adjudicating rights). If the conflict cannot be resolved or transformed by these actions, the next option is to utilize power. But that doesn't necessarily mean using coercive power (force). Rather, it means using a mix of power strategies, carefully designed to minimize coercion as much as possible, instead using a combination of integrative and exchange power to reach what we call the "optimal power strategy mix."

Gandhian "Step-Wise" Conflict Escalation

Another way to get the other side to notice a conflict and get them to take your interests and needs seriously is to copy the way Gandhi designed his pressure campaigns. Gandhi used self-limiting conflict processes that had built in devices that kept the conflict within acceptable bounds. For instance, he always escalated conflicts in a step-wise fashion, interrupting pressure campaigns with withdrawal, periods of reflection, evaluation, and repeated attempts to negotiate an acceptable outcome. If those efforts failed, he would escalate again, but then pull back, and repeat the reflection, evaluation, and negotiation process.

Gandhi also stressed the importance of maintaining personal relationships with the opponents, and, as Fisher and Ury later urged, "separating the people from the issues." He also eschewed secrecy, insisting on the open flow of information, including the sharing of his movement's plans for upcoming actions. Lastly, Gandhi's theory of "satyagraha" saw the goal of conflict being persuasion and the discovery of truth, not coercion. This shifted the framing of the conflict away from a win-lose frame to a win-win frame. Gandhi's escalating commitment was not to winning, but to the discovery of the truth of social justice--even if that discovery determined that the opponents' views were in part, or even completely, true. Truth and justice for all were the goals, not victory of one side over the other.

Avoid the "Sacrifice Trap"

It is also important to prevent the "Sacrifice Trap" (discussed briefly, above, in the description of the escalation diagram) from locking people into a continuing, destructive course of action. People often get caught in this trap because they have a tendency to escalate their commitment to a previously chosen, though failing, course of action in order to justify or 'make good on' prior investments. ("We can't give up now--we've invested too much!")

While this is a problem when it is the individual making decisions on their own behalf, it is an even bigger problem when leaders ask their constituents or followers to make huge sacrifices—even of their life—so the leader doesn't have to admit that their cause was lost, unwise, or, at least, unwinnable. While there is much evidence that shows that conflict behavior is not rational; it is largely driven by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, still, if people can see how much a conflict is hurting them, and how little chance they stand of improving their situation if they continue to fight, it might help facilitate de-escalation. (This is a necessary condition for what William Zartman calls "ripeness." ) All of this suggests that it is important to provide people with a "face-saving" way of escaping bad decisions. It is far better to sympathize with and support those honest enough to admit they've made mistakes, than it is to shame them by accusing them of "flip-flopping," which is a taken to be a sign of weakness and untrustworthiness in American politics.

Defeating Over-Simplification

Just as de-escalation is started by growing awareness of the problem, the same is true of the tendency to over-simplify complex conflicts into us-verus-them narratives where "we" are the "good guys" and "they" are the "bad guys." We discussed this problem extensively in Part 2 of the Constructive Conflict Guide, and will delve into the fact-finding and communication aspects of it more in Part 4B. So we will just give a few key ideas here.

First, rather than going along with the assumption that "they" are the problem, and everything would be fine if "they" either understood the truth, came around to our point of view, were resoundingly defeated, or simply disappeared, it is important to find out what is really going on. In almost all cases, "they" are not going to do any of the things just listed, as they think exactly the same way about you. Most often also, all sides are in some way contributing to the problem, by doing things that unnecessarily drive the escalation spiral. (The example cited earlier was the campaign to "defund the police" when complete elimination of the police is not what was being suggested. The language, in that case, was unnecessarily alarming, and just created enemies among people who might have been allies in the broader campaign for police reform and accountability.)

In addition, since most people get their news from a relatively few number of preferred (and often biased) sources, they are often incorrect in some of their beliefs. We all would benefit from looking at more sources of information from a diversity of viewpoints—and that, I should note in this day and age of "Critical Race Theory" does not just mean viewpoints of people of color or other oppressed groups. It means the viewpoints of white, male Republicans too. We should consider the problem (and "the other") with an open mind—with respect to what is going wrong, and what is needed to fix it.

We discuss how to do this in much more detail in Part 4B: Promoting Understanding by Improving Fact-Finding and Communication.

Turning Down the Heat

Taking the steps listed above to try to "complexify" overly simple-narratives is a first step in de-escalation or what I'm calling here "Turning Down the Heat." But there are many more things that people can do as well. These include the following.

Pick Your Fights

Let things go when you can. Not every provocation needs to be responded to in kind. If the issue isn't important to you, don't turn it into a tit-for-tat driver of escalation Ignore it; oftentimes it will just go away. And if it doesn't, try cooperation, or simple listening, first. As we will point out in Part 4B, sometimes having someone empathically listen is enough to get people to calm down a lot. It might not resolve the entire conflict, but it often changes the tone, and the willingness of the other side to listen to your views and negotiate a mutually-acceptable outcome.

It is also important to remember that the time, energy, and resources we each have available to participate in civic debate is limited. We, therefore, ought to concentrate our efforts on places where we can really help make things better and not get caught up in the amplification of destructive escalation spirals (something that is all too easy to do on social media).

Reframing the Problem

As I said above, it is very helpful to reframe the problem so that you no longer define the problem as being the other side, but rather the destructive conflict dynamics, such as escalation and polarization, that are causing you and people on the other side to behave in ways that are preventing problem-solving, rather than enhancing it. Once you define the problem as conflict escalation (or "hyper-polarization" as it is being called with respect to U.S. politics these days), then you realize that there are much more effective strategies for solving the problem than just pushing harder and harder against the other side. It even suggests that collaborating with the other side to change conflict interaction patterns and to push back against bad-faith actors who intentionally drive escalation is helpful. Increasing numbers of scholars and pundits seem to be making such arguments now (in late 2021), one example being Peter Coleman, in his new book The Way Out.

Stop Blaming the Other

A closely-related way to reframe the problem is to stop framing the problem as created by "the other," and acknowledging that the problem is likely created, to varying degrees, by everyone, including oneself. Typically, in intractable conflicts, people on all sides assert (and believe) that the other side is evil, greedy, stupid, or wrong, and that they are right, good, and generous. Even if that is true, it seldom helps resolve the conflict—it just leads to an escalating conflict spiral.

A better approach is that suggested by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen, in their book Difficult Conversations. They make the distinction between "blame" and "contribution," where blame judges the other side and looks backwards. Contribution looks for understanding how everyone contributed to creating the present situation. It goes both backwards to see how the situation got to be and forward to figure out how to fix it. Focusing on contribution thus enables learning and problem solving, while blame causes conflicts to become more escalated and intractable.

Use De-escalatory Language

I-statements: We will talk about this more in Part 4B, but the basic idea is to try hard to use language that calms things down, and gets one listened to, not written off or responded to hostilely. One commonly taught way to do this is to use "I-statements," not "You-statements. I statements usually start with "I feel" or I felt" rather than "you did." So, instead of saying someone else did something wrong ("You ignored me!"), say how you are impacted: "I felt confused and disappointed when I wasn't able to reach you in time for us to meet."

Or, as another example, instead of calling for "defunding the police," (which implies that the all police are doing something wrong), one might use an I-message to explain one's thoughts in more detail. Such as" "I am very concerned about police excessive use of force. I think that we need to examine how police are responding to different kinds of calls, so we can figure out what we can do to make them more effective and sensitive to community needs. In some situations it might be appropriate to get help from social workers, psychologists or other crisis responders instead of, or in addition to, the police. And, I want to hear from police officers about how they view this problem, about the pressures that they face, and about reforms that they think would help them better serve the community." This, as I understand it, is really what "defund the police" really means to many people. So why not say it that way, which is a position to which many more people are likely to agree?

Empathic Listening: As we discussed above, listening is a powerful alternative to knee-jerk escalation. As we will explain in more detail in Part 4B, listening empathically does not mean you have to agree with what the other person is saying. It just means you have to show them that you heard them and properly understood what they were saying. Often, one of the main grievances of lower-party people is that they believe that no one is listening to them or cares about what they have to say. Empathic listening shows that you have heard them, and you DO care what they have to say. That can go a long way toward de-escalating a tense situation, and might even get them to listen to—and really hear—you.

Control Rumors

When a "triggering incident" happens, rumors, often false and exaggerated, spread quickly. This can turn a relatively minor incident into a significant event, even a major crisis. To prevent inaccurate and inflammatory rumors from spreading, community leaders need to set up communication systems to monitor rumor transmission, check veracity, and disseminate credible contrary information when warranted. For example, one technique the Community Relations Service has used to prevent civil rights conflicts to escalate out of control is to set up rumor-control teams composed of trusted community leaders. These leaders agree to be available by phone 24/7 and when called, quickly check to see if rumors are accurate or not. They then report what they learn (from credible sources) about what has been going on, and if mistakes were made, what steps are being taken to address the situation. This not only defuses dangerous rumors, it sets up a process that encourages officials to do the right thing.

Cooling-Off Periods

Cooling-off periods are common tools used in some circumstances to try to give people time to calm down and think before they do something in anger that that they are likely to regret. Cooling-off periods are often legally required, for example, before a union can strike, before someone can buy a gun, or before someone can obtain an abortion. But they are useful in many more circumstances than those legally required. Whenever you become angry at another person, it helps to do what William Ury described, in his book Getting Past No, as "going to the balcony." Step back, and (metaphorically, from above), look down at the situation. Look at what just happened and why. How did you contribute to the situation? How did they? What are you really looking for in this exchange? Are you looking for further fighting—or are you looking at a solution to the problem? How much does the relationship mean to you? Is it worth working to save it? Is there another way to pursue your interests and needs that will not be as confrontational? Most often when one "goes to the balcony," one is able to see a better way forward than continued conflict escalation.

Utilize Third Siders

William Ury and Joshua Weiss have developed the notion of "Third Siders." These are people—both disputants (insiders) and third parties (outsiders) who want to de-escalate a conflict and make it more constructive. Ury and Weiss say that there are ten different "third side roles" that are arranged in three categories: prevention, resolution, and containment.

The first line of defense, they assert, is prevention, which includes three roles. Providers can reduce underlying tensions by helping assure that the parties are able to meet their fundamental human needs, which often drive conflicts when they are absent. Teachers give people better conflict resolution skills, so they understand how to solve problems collaboratively and know that such approaches are usually better than coercive power-based strategies. Bridge-builders work to bring people together, so they can break down their us-versus-them, overly simplified stereotypes, and come to understand the validity of everyone's point of view.

But, Ury and Weiss admit, sometimes prevention doesn't work or doesn't happen in time, so the next line of defense is resolution. Of course, intractable conflicts are ones that have resisted resolution for quite some time, but nevertheless, there often are roles for mediators who can help work through some of the negotiable disputes within the context of wider intractable conflicts. Arbiters (often called arbitrators) can, like judges, make decisions for the parties about right and wrong and who must do what. Again, they probably will not have the authority or legitimacy to settle the entire conflict, but there might be some disputes within the broader conflict context that could successfully be arbitrated or adjudicated. (Ury and Weiss include adjudication in this category.) For example, abortion has been an intractable conflict within the United States for a long time. Yet there have been a long series of court cases that have adjudicated various aspects of this conflict, and have established limits of what people can and cannot do in pursuit of their overall goals with respect to this issue. Another resolution role is the equalizer. Equalizers work to empower low-power groups so that they can advocate for themselves more effectively (and without further escalating the conflict). And, finally, healers can help to heal past wounds and address grievances, so they don't build up and continue to strengthen the escalation spiral.

When resolution doesn't work, three more third-side roles, which Ury and Weiss label as "containment roles," can be brought into play. First are peacekeepers, who simply separate the parties and keep them from fighting (thereby stopping continued escalation). Second are referees, who keep the fighting that happens contained within norms of legitimate fighting. Third are witnesses who accurately report on what happens to the larger society to stop rumors and to make sure that people who are inclined to take illegitimate actions know they are being watched. (This, in theory, increases the costs to them for violating community norms or breaking agreements, and thereby discourages such behavior.)

In ways that are similar to our call for "massively parallel peacebuilding" to transform intractable conflicts, Ury and Weiss argue that if all ten third-side roles are widely deployed at the same time in a conflict, that conflict will most certainly become less destructive, and may even be transformed or resolved. The problem is, they assert, that it is very unusual for all ten roles to be used at once, and at a scale necessary to really have widespread impact.

De-escalating Gestures and Breaking Stereotypes

De-escalating gestures or disarming behaviors are behaviors undertaken by one side of a conflict that are unexpected, and show a greater willingness to compromise or to listen to or respect the other side than is generally expected. One of the best-known examples of such a gesture was the October 1978 visit of the President of Egypt, Anwar al-Sadat, to Israel. Sadat's visit ran contrary to all other Arab policy. Until then, all Arab governments had refused official recognition of Israel and had avoided direct official contacts. But when Sadat offered to come to Israel and speak to the Israeli Knesset (the Israeli legislature) , his offer was quickly accepted. Sadat was warmly greeted by Israeli officials and by enthusiastic crowds.[1] Bilateral negotiations between Israel and Egypt then began, but they soon reached a stalemate. Nevertheless, with the mediation of U.S. President Jimmy Carter, a peace treaty was reached and signed in 1979 and it has held ever since.

The key element of such de-escalating gestures is that they breakdown the "evil other" stereotype, and make "the other" seem like a person or group of people that you could actually work with. Sometimes such gestures are made overtly and publicly, as was true with Sadat's visit to Israel, or South Africa's unconditional release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990. Other times they are private. Before Mandela was released, for example, white leaders from South Africa met with leaders from the outlawed black African National Congress outside the country. This facilitated Mandela's release, and also led to the willingness of the ANC to proclaim (as explained by Ebrahim Rasool) that "South Africa belonged to all who lived there."

If de-escalating gestures can be linked together, they can enable what Charles Osgood referred to as GRIT -- the Gradual Reduction in Tension. With GRIT, one side announces and initiates a series of small cooperative moves, and invites the other side to reciprocate. If the opponent responds positively, the first party makes a second concession, which sets a "peace spiral" in motion. If the first initiative is ignored, on the other hand, it can be followed by a second or even a third attempt. These concessions should be designed to build trust and indicate a willingness to cooperate, but should not be terribly costly. If they succeed, everyone will be better off. If they fail, not much is lost.

Trust Earning / Confidence Building

In intractable conflicts, trust between disputants is usually completely absent, and rebuilding trust is a much longer and slower process than losing trust in the first place (which can happen very quickly). To re-earn trust, one must engage in a lengthy series of confidence-building measures (as discussed immediately above) and other steps to prove that one is worthy of being trusted. Among these are both sides indicating a desire and willingness to rebuild the relationship, recognizing and working to make amends for the harms done, and both sides taking slow steps to regain each others' confidence. When this is done successfully, the previously hostile parties can begin to develop a working relationship and can, over time, work to mend the emotional scars built up over the years of conflict. Ideally, disputants can start to build what Lewicki and Tomlinson call "identification-based trust," which is not just based on rational calculations about whether the other party is good to it's word, but an emotional connection between the parties, based on a sense of shared goals and values.

Respect and Face

I (Heidi) used to teach a semester-long undergraduate conflict skills class. At the end, I told the students, if they only remembered two words from the class five or ten years later, the two words should be "respect," and "listen." Listening we will talk about briefly below (and in detail in Section 4B on Facts and Communication). Respect I'll talk about here.

Respect can be defined and enacted in a variety of different ways, but most importantly, it means treating others with dignity. It is the opposite of humiliation and contempt. As William Ury writes in his book The Third Side: "Human beings have a host of emotional needs—for love and recognition, for belonging and identity, for purpose and meaning to lives. If all these needs had to be subsumed in one word, it might be respect." When respect is absent, when people are humiliated, they tend to lash back. Evelin Lindner, probably the world's leading expert on humiliation has long called it "atom bomb of emotions," as it blows relationships up. Respect, on the other hand, builds relationships. People respond positively when treated positively, and they are much more likely to treat you with respect if you treat them that way.

But, as I taught in my class, even if respect is not reciprocated, even if people have engaged in bad behaviors and do not deserve respect, it usually helps to give it to them anyway. It goes a long way towards stopping the escalation spiral, and may even, over time, get the bad actors to change their approach to you, as they see you more as a worthy human, and less as a worthless opponent. Now, whether such is true of the most manipulative and cynical bad-faith actors is a matter of dispute, and we do not have room to discuss that here. Certainly there is value in calling out bad behavior, and working to stop it where it occurs. But even that can usually be done in a respectful way, rather than in a humiliating way which is almost certain to drive the escalation spiral higher. Here, one of Fisher, Ury, and Patton's principles from their long best-selling book Getting to Yes, applies, "focus on the issues, not the people." Or, in this context, attack the unacceptable things that people are doing, rather than attacking the people themselves.

Face is a concept that is very closely related to respect—it is one's self image, and the image one tries to project to the world. All people, I would argue, have a strong desire to "save face," meaning they want to look good to others, and not look foolish, weak, or mistaken. Cultural experts often assert that "high-context cultures" (such as Korea, China, Japan, as well as some Middle-Eastern and Latin American countries) place a higher value on face than do "low-context cultures" (such as the U.S. and other Western countries). Losing face before one's group in high-context cultures, says Raymond Cohen in Negotiating Across Cultures. Communications Obstacles in International Diplomacy, can be "a fate worse than death" (p. 30).

So "giving face," not humiliating people, allowing them a face-saving way out of a mistake, rather than making a big deal about it, or insisting on massive retaliation, is also much more likely to result in mutually-acceptable outcomes and de-escalation of the conflict. Plus, the willingness to acknowledge and correct mistakes is a virtue that we should all have an interest in cultivating.

Giving Everyone A Future They Can Live With

We will talk about this in detail in Section 4C on visioning, but briefly, if you want to convince the other side to stop fighting, you need to give them hope that, if they work with you, they will be able to get a future that they in which they would want to live. The most clear example of the importance of this is the difference between the end of World War I and the end of World War II. The Treaty of Versailles, at the end of World War I was so punitive against the Germans that it left them angry and vengeful. While certainly not the only factor that led to World War II, it certainly was a major contributing factor to the rise of Hitler and the Third Reich. World War II, on the other hand, ended in Europe with the Marshall Plan, which helped rebuild Europe, and a similar program which was implemented in Japan. Though Germany was still forced to pay reparations, they were not as severe as those after World War I, and were off-set by the assistance they got from the Marshall plan, which enabled economic, political, and social recovery. This facilitated growing cooperation within much of Europe (excluding areas controlled by the Soviet Union, which were not part of the Marshall Plan), which eventually lead to the formation of the European Union, instead of a third world war.

Using the Optimal "Power Strategy Mix"

Power is usually thought of as force—the way the stronger party can use coercion to force the weaker party to do something they otherwise wouldn't want to do. But power can take other forms too: In his book, Three Faces of Power, Kenneth Boulding referred to coercive power (a threat: "you do that or else!"), exchange power (negotiation: "if you do that, I'll do this") and integrative power (respect: "I'll do that for you because I respect you or I care about you."). Integrative power, he explained, is actually the most powerful of the three, because neither of the other two work without it. At the societal level, oppressors can only continue their oppressive actions if loyal people help them carry those actions out. As renown nonviolence scholar Gene Sharp points out, the widespread non-cooperation of followers can undo any tyrant. And exchange only works if people have enough respect for the process and the other side to abide by their promises. If they don't, the exchange or negotiation will quickly break down.

So the key notion here is that these three power strategies are always used in some combination. In order to de-escalate conflicts, disputants are well advised to use as much integrative and exchange power as possible, and as little threat or force as they can. As we explain in the video on the power strategy mix, it helps to analyze the character of the parties you are trying to influence. Are they "persuadable"? If so, they will likely respond best to integrative power. Are they willing to negotiate? If so, they will likely respond best to exchange power (with a dash of integrative power mixed in to hold the negotiation together). A relatively small number of people are what we all "incorrigibles"—people who absolutely, positively refuse to budge. Those people will need to be persuaded with threats, but again it helps to use as little coercion as possible and mix in with it exchange and respect (integrative power) as we talked about above in the sections on Constructive Confrontation and Gandhi's step-wise escalation. Finding the optimal mix of power strategies will help get what you want/need while creating as little backlash as possible.

Conclusion

All of these strategies can work together to help reverse overly simple and inaccurate us-versus-them framing of the conflict, and the resulting conflict polarization and escalation. As we noted at the beginning of this section, we view escalation as the most destructive force on the planet. So figuring out how to avoid it, when possible, and reversing it once it has started, is of the highest importance. This section shows that there are many ways to do this. We just have to decide that we want to these things, start working on them, don't give up as we face obstacles (because we will), and bring as many people as we can along with us.

------------------

1 As I write this, I am reminded of Donald Trump's statement about the white-supremacists' protests in Charolotteville, VA in 2017. When asked what he thought about those events, he responded that there were "very fine people, on both sides." I am not agreeing with that—the people who took part in that protest, from what I could tell, were not behaving at all like "very fine people." But there are good people in the U.S., on both the Left and the Right, who legitimately disagree about what should be done about racial inequities in the country. And there are bad people on both sides too. We need to look more deeply into what people believe and advocate and why, before we can start assessing who is "good," who is "bad," and what policies being advocated are good or bad.