The King Soopers Shooting: This Time It Was Personal

By Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess

March 29, 2021

Coming Home...To Terror

Heidi and I have been off for three weeks, visiting her aging dad after 12 months of COVID19-enforced separation. That’s why you haven’t seen many BI posts, or a newsletter for several weeks. Shockingly (to us), just minutes after we got home to our house in Boulder, Colorado, on Monday March 23, a gunman opened fire at the grocery store ½ mile away--between the time when Heidi and I had placed a grocery order and the time that we were scheduled to pick it up. In other words, the shooting occurred during the time when one of the many "essential workers" who have made it possible for us to weather the pandemic in isolation, and relative safety, was doing our shopping for us.

While Kings, as we call it, is a grocery superstore run by Kroger, the store is also, in a sociological sense, the kind of neighborhood market that has always played a central role in binding communities together. In the almost 50 years that we have been patronizing the store, it has been a place where we would run into parents whose kids attended school with ours. It has been a place for refreshing connections with those with whom we have debated so many civic issues. More recently, it has been a place where we catch up with the parents of our now-grown children and learn about the exploits of their kids and, now, grandkids. It is also a store that has been staffed with long-term employees who we have depended upon, appreciated, and watched age with the rest of us. Marketplaces like this are the one place where people connect as part of the everyday business of living in a shared community—communities that are very real, despite the all-too-frequent protestations to the contrary.

It became clear that something was very wrong when what seemed like an endless barrage of sirens was followed by a reverse 911 call that activated every electronic device we own. Helicopters flew overhead, as air ambulances assembled in the park across the street (ambulances that, sadly, were never used). Thankfully, we and our closest friends escaped physically unharmed. Psychologically, the harm is palpable. And we shudder when we think of the suffering of the many others in our community who were closer to the carnage: the victims themselves and their families, other grocers, pharmacists, shoppers, checkers, and the myriad of people who work in or were shopping at Kings Monday afternoon.

| The King Soopers shooting was a direct attack on the very fiber of our community by someone who, for some reason, decided that they hated us enough to justify indiscriminate killing. |

The impact on the community, we are sure, will be far-reaching. This isn't the type of disaster where the police and fire trucks go home and everything returns to normal. It also isn't like the terrible flood we suffered a few years ago or the increasingly frequent close calls we've had with potentially catastrophic wildfires. It was a direct attack on the very fiber of our community by someone who, for some reason, decided that they hated us enough to justify indiscriminate killing.

This kind of tragedy is, of course, not new. In 1999, when our kids were in high school, Guy was serving on our high school's parent / faculty governing board at the time of the Columbine shooting just down the road in west Denver. We all, sadly, are familiar with a long litany of similar tragedies. The point, which Monday’s close call emphasized to us once again, is that these events are a terrifying symptom of the more general destruction of the social fabric that threatens pretty much everything and everyone that we care about.

Preliminary Conclusions

We probably won't have reliable information about the motivations behind the Boulder attack for some time, and we should resist the tendency of people to twist what little we do know in ways that support some predetermined and politically-useful narrative. Still, in looking back at the longer history of mass shootings and the many ways in which our social fabric is unraveling, we think we can draw some important conclusions.

| Our society is producing far too many alienated people who have concluded that society is so hopelessly corrupt and worthless that attacks on the very fabric of society and, especially, the elites, are justified. |

First, it is clear that our society is producing far too many alienated people who have concluded that society is so hopelessly corrupt and worthless that attacks on the very fabric of society and, especially, the elites, are justified.

This is a problem that is compounded by the disgraceful way in which we, as a society, fail to adequately care for those with serious mental health issues. While almost all of these individuals confine their attacks to nonviolent expressions of anger and hostility, there are a disturbing number of cases in which resentments emerge as overt acts of violence (including mass shootings and violent protests). The frustrations and resentments of those who feel that they have been left behind or trod upon by society are also, not surprisingly, a major source of the energy behind populist revolts on both the left and the right that are helping to unravel our democracy.

| Many of these individuals have good reason for believing that society has failed them. We need to find effective ways of drawing these people back into the social fabric in ways that address their many legitimate grievances and offer them a realistic path to a respected, dignified role in society. |

The key to addressing this alienation is to recognize, first of all, that many of these individuals have good reason for believing that society has failed them and that they are, in myriad ways, being exploited by society's elites. The solution, which is obviously a big challenge, is to find effective ways of drawing these people back into the social fabric in ways that address their many legitimate grievances and offer them a realistic path to a respected, dignified role in society. Such paths need to be available to everyone, not just the successful few who manage to join the ranks of the elite. Continuing to view disaffected citizens with scorn and contempt will only compound their frustrations and worsen the alienation problem. We need to take vastly more effective steps to reverse our long slide toward an economy that concentrates wealth in the hands of the super-rich and denies more and more citizens a path to economic security and respect.

These are, of course, longer-term solutions. Over the shorter term, we need to enforce the rule of law in ways that reverse escalating criminal violence (including mass shootings).But we must also enact policies that prevent and deter police violence and deal effectively with the broader problem of “systemic racism.” That does not mean, however, completely “defunding the police,” as was widely proposed after the George Floyd shooting last summer. Looking now at the way the King Soopers shooting ended, we are deeply grateful that the City of Boulder did not “defund” its police (though that was proposed, both on campus with respect to the University of Colorado police, and to City Council regarding the city police department.) Had there not been such a quick and forceful police response, the gunman, likely, would have killed many more people. (Eric Talley, the first police officer to arrive on the scene was killed as he fought to protect others.) Clearly, the police have an important role to play in communities, but they must equally protect all citizens, and be trusted by their communities to do so fairly and professionally.

| We also, clearly, need to do something about the widespread and easy availability of guns, and, especially, military-style weaponry. There are ways to do this that are less likely to provoke the ire of the gun-rights advocates than the proposals made in the past. |

We also, clearly, need to do something about the widespread and easy availability of guns, and, especially, military-style weaponry. The U.S. has more guns per capita than any other country by a factor of two and we exceed most countries by a factor of four or more. According to a report by Christopher Ingraham of the Washington Post, “The gun ownership rate in the United States is more than six times higher than the average among similar wealthy nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.” We do not, fortunately, also lead the world in gun violence deaths– we are “only” 32nd highest at 3.96 deaths per 100,000 people in 2019. But that still is eight times higher than our neighboring Canada, and nearly 100 times higher than the U.K.

Although America has been strikingly unsuccessful in tightening its permissive gun laws, New York Times columnist, Nicholas Kristof argues that there are a number of realistic steps that could be taken to limit the horrific costs of gun violence (not just the relatively minor problem of mass shootings). What's especially attractive about Kristof's approach is that he avoids the progressives’ common trap of demonizing and alienating gun owners and pushing superficially attractive policies (like the earlier assault weapons ban the didn't really understand or successfully address the problem). Instead, he argues that we should license guns and gun owners the same way we do automobiles and automobile drivers. He points out that:

Gun enthusiasts often protest: Cars kill about as many people as guns, and we don’t ban them! No, but automobiles are actually a model for the public health approach I’m suggesting.

We don’t ban cars, but we work hard to regulate them — and limit access to them — so as to reduce the death toll they cause. This has been spectacularly successful, reducing the death rate per 100 million miles driven by 95 percent since 1921.

Kristof doesn’t go into as much detail as I would, though his point is clear. Drivers have to pass tests before they are allowed to drive. Automobile manufacturers are required to install a variety of safety devices (seatbelts and airbags, for instance), and drivers are legally required to use them. Why can’t we require gun purchasers to pass a gun owner’s test and both gun owners and gun manufacturers to implement safety measures (such as, keeping guns unloaded and locked up, for example, and manufacturing smart guns that will not fire unless they are being held by the owner, thereby preventing accidental firing by children).

Our inability to enact pretty much any of Kristof's common-sense proposals raises the obvious question, why? The problem is that the gun-control debate has been weaponized by political campaigns on both the left and the right as a way of mobilizing the all-important "base voters” that they need to win elections. It has reached the point where guns are now one of the central fault lines defining our hyper-polarized politics.

When asked about gun control in his first Presidential news conference three days after the King Soopers shooting (and just a few more days after an equally horrendous shooting in Atlanta, Georgia), Biden evaded. While he has long advocated gun control, he pointed out that he is a practical man, and that other issues were higher priority to tackle first. What he also understands is that gun legislation is going to be exceedingly difficult to enact, and he wants to rack up as many “wins” as possible early in his presidency. Besides, a big gun control push would likely inspire a powerful backlash among gun rights advocates who see guns as essential to protecting themselves in an increasingly dangerous world. This could, of course, threaten Democratic prospects in 2022. We also need to find effective ways to push back against those in the media, the firearms industry, and politics who have figured out how they can profit by exploiting the issue in ways that undermine the ability of the larger society to sensibly address the gun-violence problem.

| We need to address the widespread distrust of institutions essential to a functioning democracy which includes, not just government institutions, but also the media. One reason that people feel a need to buy guns is that they have little confidence that their local police departments will keep them safe or will look out after their interests. |

Lastly, we need to address the widespread distrust of institutions essential to a functioning democracy which includes, not just government institutions, but also the media. One reason (of many, of course) that people feel a need to buy guns is that they have little confidence that their local police departments will keep them safe or will look out after their interests. Indeed, after mass shootings, gun purchases typically go up significantly. There was also a surge in gun sales following last year’s contentious election, pandemic-related uncertainties, and George Floyd-related protests. Further worrying is the possibility that we may be entering something of an arms race with Blacks and other left-leaning groups who are increasingly acquiring guns in response to perceived threats from the right, the police, and social collapse.

Also driving these spikes in gun purchases is the fear that, in response to the violence, the government will finally act to limit access to guns. This is of grave concern to those who believe that they need guns to keep themselves safe. The question of whether gun ownership actually makes people more secure is, of course, hotly debated and a major focus of gun-related conflict.

| The efficacy of guns to keep one's family safe would be a good topic to investigate jointly using data mediation or joint fact finding |

This would be a good topic to submit to what we term “data mediation” or “joint fact-finding” in which both sides cooperate on a study to determine the facts (which, in this case, should be empirically verifiable). If both sides agree on the experts and the investigation process, they are more likely to accept the results. As it is, the Left believes myriad studies such as the one done by the Harvard School of Public Health that argues that guns make us less safe. But gun-rights advocates still preach the opposite. According to Amy Swearer, writing in The National Interest, “as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2013, almost all major studies on defensive gun uses have concluded that Americans use their firearms in defense of themselves or others between 500,000 and 3 million times every year, far outpacing the number of times firearms are used to harm innocent people.” (It should be noted that there was no citation for this assertion.) How are Americans to know what to believe? They can’t. So they believe the articles that tell them what they want to hear. The National Interest article, however, does confirm facts also asserted by the left: that the number of guns in this country has increased significantly over the past few decades, and more Americans than ever have concealed carry permits and carry on a regular basis.

What the article doesn’t mention is the aggressiveness of some of the gun advocates—for example Rep. Lauren Boebert trying to carry her Glock onto the floor of Congress, pro-gun activists threatening to kill a state lawmaker in Virginia, armed demonstrators carrying firearms into the Michigan State Capitol Building and heckling lawmakers from the spectator gallery, and, of course, the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, which involved much more than angst about gun control, of course, but it illustrated the protestors’ readiness to do harm to our lawmakers and other public officers (such as police).

| The general public has come to hate “the other” more than we used to. Combine that with easy availability of powerful firearms--and you get a recipe for disaster. |

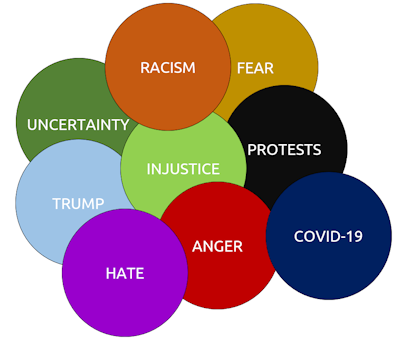

This is driven, at least in part, by the fact that the general public has come to hate “the other” more than we used to. Donald Trump built his political movement around the amplification of long-simmering social tensions to the point where his principal goal seemed to be to "make [the hated] liberals cry." On the left, there has been a relentless campaign to hold “un-woke,” white, “racists” responsible for all that is wrong with society (including mass shootings). The net effect is to increasingly encourage people on both sides of the political divide to hate one another and, more generally, to view all of our problems as someone else’s fault. While we are not fans of the "cancel culture," we do think that there is a place for public condemnation of those who seek to divide society by focusing exclusively on the things that divide us and neglecting the many things that unite us (something that the cancel culture, of course, often does).

We now live in a society in which pretty much anyone can easily obtain powerful firearms. Put this together with a society in which we are all encouraged to view many of our fellow citizens as fundamentally evil, and we have a recipe for disaster. New York Times’ opinion columnist Nick Kristof wrote an article recently about “one famous evangelical leader [who] has called on Christians to arm themselves for an inevitable civil war against liberals, who, he suggests are allies of the devil.” In this context it is not at all surprising to see some people resort to violence. This is a tendency that is exacerbated by the fact that there will, inevitably, be a few people with severe psychological problems and a sense of alienation that is so extreme that they conclude they have nothing to live for other than to try to destroy as much of the society they hate as possible.

What We Need To Do

| We desperately need to dial back the inflammatory rhetoric and work to start reconciling our deeply-divided society in ways that promise people from left and right-leaning cultural orientations a future in which they would really like to live. |

What we desperately need is to dial back the inflammatory rhetoric and really work to start reconciling our deeply-divided society in ways that promise people from left and right-leaning cultural orientations a future in which they would really like to live. In addition, we need to treat everyone with respect (even those we do not think deserve it), and make it possible for them to meet their fundamental human needs. That means accepting their identity without disdain, allowing them to practice their religion and live their values (as long as they aren’t hurting others) and have the security of a loving family, home, education, a job that earns a living wage, and health care (among others).

Those of us with an interest in conflict and peacebuilding fields need to redouble our efforts to find a way to bridge the political divides in this country to help people find security and hope. We must help the U.S. rebuild a sense of community, and a desire to work together to confront our many pressing problems—including gun violence and systemic racism, among many others.

It is clear that doubling down on hostile confrontational tactics—even when they seem “justified” by the need for “justice”— is only going to deepen the mutual hatred that is at the core of our problems. It isn’t going to persuade the other side that we are right. It likely isn’t even going to “win justice” because it will be fought every step of the way by those who define “justice” differently.

If we want to avoid much more violence and, potentially, large-scale civil unrest, we need to work together with “the others” to meet our many shared challenges. We do need to examine and acknowledge the truth about our past (examining both the virtues and the wrongs done by all parties, not just the White elite.) And we need to work towards a future society built on mutual understanding, fellowship, and one in which the human needs of everyone on both the left and the right (and in between) are truly met.

| It's time to act as if our own life and the lives of people we care about are at stake. Last week, we found out that they are. |

It's time to act as if our own life and the lives of people we care about are at stake. Last week, we found out that they are.

For those interested in getting involved in this effort who are not yet working in the field, the larger Beyond Intractability system offers a wealth of information on the many things you can do to help.

* This blog is a duplicate of the essay at the beginning of Newsletter #41, but since blogs are slightly more "permanent" than newsletters (though past newsletters are available in our Newsletter Archive), I decided to make this essay a blog post too.