Addressing The "Grey Zone*" Warfare Threat to Negotiation

By

Guy Burgess

February 2, 2022

| Authors Note: This essay was prepared in conjunction with the Project Seshat exploration of strategies for countering the now widespread use of "gray-zone*" warfare tactics to sabotage a wide range of negotiation processes. We are also posting it on Beyond Intractability because it directly addresses our interest in understanding and finding better ways of addressing the disruptive effects of "bad-faith actors" (in this case geopolitical rivals) who are trying to make our conflicts more intractable. |

At this point, we think that it is pretty clear that "gray-zone" tactics are now being widely used to sabotage a wide range of negotiations in ways that may make many mutually beneficial agreements impossible. Such efforts are a direct assault on the viability of liberal democracies and the "invisible hand" that has made capitalism so successful.

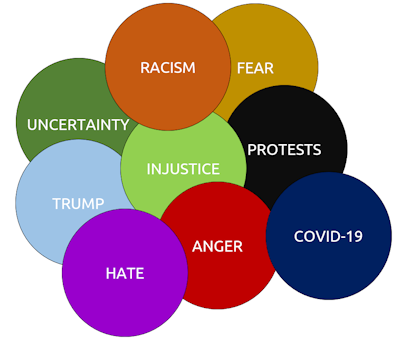

While the modest use of some gray-zone tactics may be forgiven as an inevitable part of hardball bargaining in a turbulent environment, the threat that we are concerned about arises from large-scale attacks perpetrated by state-level actors, as well as similar attacks emerging from intertwined global networks of corrupt private-sector interests. The same individuals and organizations have also been engaged in broader attacks on democratic societies, where they have been quite successful at using a variety of divide-and-conquer, destabilization tactics to inflame tensions and drive the hyper-polarization spiral. It is hard to look at this constellation of attacks and not come to the conclusion that we are facing (at least from a US perspective) a kind of 21st-century Pearl Harbor—only this time most people don't even seem to have noticed that they are being attacked. (Much, and probably most, of this political dysfunction is, of course, attributable to domestic forces. Still, it is quite likely that these outside forces are also playing a significant role.)

| Far too many leaders (and citizens) are willing to embrace gray-zone tactics, as long as they appear to favor their own interests. |

Before addressing Seshat's big question about how we should train negotiators to operate in this environment, we need to come to terms with the fact that, as negotiators, and as national and international communities, we are not really clear about what the objective of this training should be. One of the most insidious by-products of these hyper-polarization and de-stabilization campaigns is that they have helped to so undermine the sense of common purpose that used to be shared by liberal democracies that we no longer seem to agree on what we ought to be defending. Instead, it seems that far too many leaders (and citizens) are willing to embrace gray-zone tactics, as long as they appear to favor their own interests. They only condemn such tactics when they are seen as favoring the other side. This has the effect of focusing all of the blame for anti-democratic, gray-zone tactics on the opposing side of the political divide—an action that, predictably, intensifies the escalation spiral and compounds the problem. What people are missing is the fact that those who are behind all of this have a completely different and corrupt agenda that is deeply threatening to both the interests of the left and the right.

| Bad-faith actors have incorporated into their gray-zone tactics efforts to discredit any possible attempts to objectively determine the nature and magnitude of such attacks. This makes it much harder to build the kind of consensus needed to mount a coordinated and effective response. |

A big part of how they get away with all of this is that they have incorporated into their gray-zone tactics efforts to discredit any possible attempts to objectively determine the nature and magnitude of such attacks. This, in turn, makes it much harder to build the kind of consensus needed to mount a coordinated and effective response.

These are obviously all very serious problems—not the kind of thing that can be fixed with relatively minor tweaks in negotiation strategy (or the training and continuing education of negotiators). That said, there are things that could be done to make negotiators more aware of the larger problem and the various ways in which it might undermine their efforts. We need to help negotiators to become much more aware of the various gray-zone tactics that they are likely to face. And, as they do this, negotiators need to learn how to work in a rapidly changing "battle space," where bad-faith actors can be expected to work hard to develop and implement evermore creative and effective tactics. Negotiators also need to understand that tomorrow's gray-zone warfare is likely differ substantially from contemporary versions. They need to be taught vigilance, flexibility, and imagination so that they can identify and correct vulnerabilities before an adversary finds a way to exploit those vulnerabilities.

It would surprise me if there are many (or, maybe, any) negotiation training and education programs that are adequately addressing this problem. This suggests that there is a critical need to pull together highly interdisciplinary teams (such as the one assembled for the Seshat Project) and then set about the task of developing curricula that better address these issues.

| We need to find some way to move beyond today's hyper-polarized, us-vs-them, left-vs-right political frame. We have to quit seeing virtually everything in partisan political terms and losing sight of the fact that we all have an interest in defending the liberal democracies (and associated capitalist institutions) in which our partisan disputes can constructively play out. |

It is also important that we recognize the larger, societal dimension of the problem. Effectively mitigating the threat will require societal-level changes in several broad areas. First, we need to find some way to move beyond today's hyper-polarized, us-vs-them, left-vs-right political frame. We have to quit seeing virtually everything in partisan political terms and losing sight of the fact that we all have an interest in defending the liberal democracies (and associated capitalist institutions) in which our partisan disputes can constructively play out. If we fail to do this, we are likely to discover that our pursuit of some kind of decisive partisan victory is much more likely to result in a dystopian future that combines dysfunctional political breakdown, the rise of authoritarian leadership, large-scale civil unrest and violence, and increasing instances of intergroup domination and oppression. With its background in conflict dynamics, the negotiation field has much to contribute to this larger effort to help societies move beyond today's hyper-polarized conflicts which are, in turn, exacerbating pretty much every other problem.

| We need clearer professional standards and expectations regarding what, exactly, those working in the field are obligated to do to protect the larger society from the gray-zone threat. The moral obligations of negotiators need to be much wider than the obligation to advance the interests of whoever is paying their salary. |

Beyond this, there is a need to set clearer professional standards and expectations regarding what, exactly, those working in the field are obligated to do to protect the larger society from the gray-zone threat. The moral obligations of negotiators need to be much wider than the obligation to advance the interests of whoever is paying their salary. We need to be clear about when larger, societal interests should take precedence over the narrower interests of the parties to specific negotiations. Professional standards need to be updated to more clearly address this issue. There is also likely to be a need for some more effective enforcement process that can limit the ability of corrupt actors to use negotiation processes to advance their selfish objectives. This is a principal that's simple to state, but much harder to implement in practice. For example, there is a need for people capable of negotiating on behalf of those who have been kidnaped or who are being held for ransom in other ways. There is also a need to be able to negotiate disagreeable compromises that handle bad situations in ways that are better than available alternatives.

| This an extremely serious problem—one that is likely to worsen in the coming years. It demands a much more aggressive response from the negotiation and the broader conflict resolution and peacebuilding fields. |

The bottom line is that this an extremely serious problem—one that is likely to worsen in the coming years. It demands a much more aggressive response from the negotiation and the broader conflict resolution and peacebuilding fields.

__________

* According to the US Special Operations Command, the grey zone is defined as "competitive interactions among and within state and non-state actors that fall between the traditional war and peace duality." In other words, this is the full range of unscrupulous and usually clandestine tactics that might be used to weaken an adversary – everything short of kinetic warfare and violence.