The Massively Parallel Approach — the Key to Dealing with Scale and Complexity

Newsletter #406 — December 6, 2025

Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess

Big Picture Newsletter Series - Post 7

This newsletter is the seventh in the Big Picture Newsletter Series, in which we are trying to sum up and review some of the key themes we have been exploring over the last several years. Here we talk about what we see as the only workable option to work effectively at large scale and complexity --what we have called "Massively Parallel" approaches — to peacebuilding, problem-solving, democracy strengthening and civic renewal.

The Massively Parallel Approach

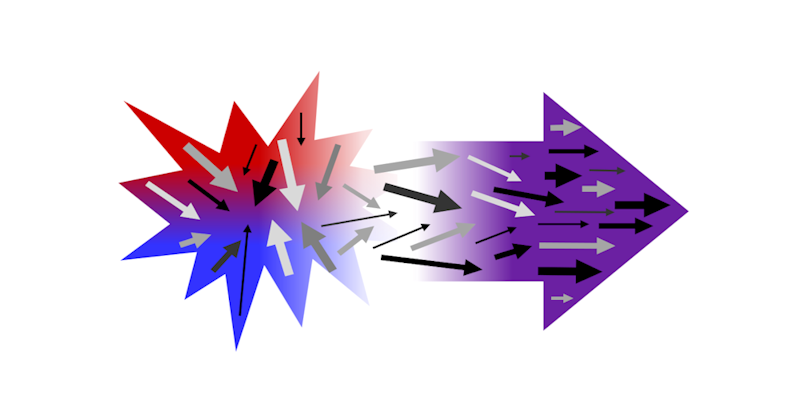

As we explained at the end of Newsletter 398, several years ago we coined the term "Massively Parallel Peacebuilding," which we later expanded to other endeavors: Massively Parallel Problem-Solving, Massively Parallel Democracy-Building), and Massively Parallel Civic Renewal. Here we will just call it the Massively Parallel approach or MP for short. The term is derived from the more common term "massively parallel computing," in which many small computers work side-by-side to solve a problem that is far too complex for a single computer to solve on its own. (This is one of the key technologies that has made the AI revolution possible.) With massively parallel peacebuilding and the other MP endeavors, many people and organizations similarly work side-by-side to solve large-scale, complex social, economic, environmental, and political problems.

We should emphasize that the MP approach is not one of our ideas that we are trying to get everyone else to adopt. Rather, it is a name that we use to describe the "emergent" meta-process that has long enabled societies to tackle highly complex, large-scale problems and conflicts. The MP framework makes it easier to see the interrelationships between the many thousands of people and organizations who are already working independently on different projects with different short-term and long-term goals, strategies and tactics. Yet they are all roughly working towards related and overlapping long-term goals, such as resisting aggression, bringing peace to war-torn regions, strengthening democracy or civic engagement in a particular country (or town), or trying to solve a particular social, economic, or environmental problem (such as unchecked immigration, poverty, or climate change).

The massively parallel approach contrasts sharply with all-too-common efforts to find some single grand solution or some political candidate that will somehow fix it all. Our social, economic, environmental, and political problems are far too complex for that. We really need a massively-parallel, division of labor-based approach — one that mobilizes our collective insights and energies to address first, our inability to work together, and second, the problems we need to work together to solve. This is the only way that humanity has ever been able to overcome the big challenges that it has faced.

Since we are dealing social systems that are complex, not complicated, there is no top-down leader or organizer with control over the entire system. Rather, social processes are "coordinated" by a process that is the social equivalent to Adam Smith's concept of an economic "invisible hand" — the notion that all problems create opportunities for people who can help solve them. It works by people first identifying problems that need fixing, most often in their local communities, but also at higher levels. Then they work with others to develop strategies for addressing those problems and test the market for their ideas. If the response is positive, they start building an organization focused on implementing their "solution." If the reaction is negative, they go back to the drawing board and try to develop more effective and attractive ideas. This is the system through which the collective judgment of all of the potential beneficiaries of each activity decides what succeeds and what fails.

Massively parallel problem-solving is the natural mobilization of large numbers of independent projects, each trying to meet a need that project participants have identified in their own communities. The MP approach enables these otherwise isolated efforts to "scale up" to have wider national effects, even when centralized top-down approaches aren’t working. (Centralized, one-size-fits-all approaches often fail because they can't adapt to the fact that different communities have differing circumstances and priorities.)

Even when people see a particular cluster of issues as problematic, they are likely to have different views about exactly what causes the problem and, therefore, what should be done about it. This is one of the big advantages of the MP approach. It doesn't force problem-solving efforts to agree on either a singular diagnosis of the problem or a singular solution. It allows the system to try many possible solutions — increasing the chances that at least a few of those solutions ultimately will prove effective. We sometimes call this the "all of the above" approach to problem-solving.

Also contributing to the power of the MP approach are the civic renewal equivalents of "trade associations" with which economists and business leaders are familiar. These organizations provide economies of scale to relatively small, local efforts by providing a framework in which they can work together in mutually supportive ways that involve various types of coordination, collaboration, and joint learning. Examples from the business world include the Computer and Communications Industry Association and the National Coffee Association. These trade associations help strengthen member businesses by, for example, pooling market research efforts, facilitating the joint development of more competitive goods and services, and lobbying the government to limit unnecessarily disruptive regulations.

Similarly, there are "trade" organizations that are working to increase the effectiveness of the many smaller projects that are, in various ways, trying to help heal our deeply divisive politics. These include the Inter-Movement Impact Project (IMIP), the Thriving Together US Initiative, the Practitioner Mobilization for Democracy (PMD), The Trust Network, and the National Association for Community Mediation, among many others. All meet regularly to allow members to network and explore collaborative ideas. They also provide resources for recruitment, training, marketing, and other “business efforts.” Braver Angels' Citizen-Led Solutions and Better Together America, along with several other organizations are developing a network of "Civic Hubs," which are helping local communities work together collaboratively to solve local problems. Both Braver Angels and BTA provide training, networking, resources, and other assistance to help these Civic Hubs be as successful as possible.

Although all these efforts are growing rapidly, they still reach only a small fraction of the people and organizations involved in the larger MP democracy building effort. The National Civic League has assembled a Health Democracy Ecosystem Map of U.S. organizations which are working in the healthy democracy area (which they define as including over 50 sub-goals such as community engagement and community building, civic education, electoral reform, organizing and advocacy, and many others). As of late October 2025, they list over 12,000 organizations in 79 different networks and coalitions. Though no one is coordinating their efforts, we would argue that they are all part of a massively parallel system which is working to create a "healthier democracy" in the United States.

Obstacles to Massively Parallel Approaches

While the number of people and organizations engaged in good-faith, massively parallel efforts to make democracy work is impressive, it faces several significant obstacles. One is funding. Most of these efforts are relatively small, and they are working as volunteer organizations or with very little funding. Their opponents, on the other hand, the bad-faith actors, who are working against collaborative democracy in an effort to establish a power-over government, are very well funded. This makes standing up to the bad-faith onslaught an especially difficult challenge.

A second obstacle is few people know about this effort or the individual actors in it. As we talked about in the newsletter on reframing our information feeds, the media is so focused on bad news, on conflict, and on how bad “the other side is,” that these bridge-building and collaborative initiatives often have little, if any, visibility. The only people who know about them are the direct participants. If these efforts can be made much more visible, they are likely to give people hope, knowing that democracy is not “doomed,” and that they, too, can and, indeed, must, become part of this massive democracy-strengthening effort. As we have said many times before, “democracy is not a spectator sport.” If we want democracy to succeed, we cannot sit on the sidelines rooting for one “team” or the other. We need to “get in the game” and start working for the issues and outcomes we care about. But, as we emphasized in our post on constructive confrontation, we need to do that in a way that pulls society together, rather than tearing it further apart.

A third obstacle is lack of coordination and cooperation. Although complex systems cannot be run in a top-down, mechanical way, they still can benefit from some coordination and cooperation among parts of the system. So, outcomes are often better when several entities pool their resources and their expertise and collaborate on particular projects. But the funding shortfall often causes different organizations that might otherwise collaborate to view other similar organizations and competitors for the same small pots of money. So they don't work together in ways that would benefit everyone; instead, they compete with each other and produce less overall benefit as a result.

Massively Parallel Democracy Building Goals

There is a lot of disagreement about the key elements of democracy and the things that must be done to revitalize it. These disagreements reflect differing priorities and differing areas of focus. Still, when we think about them as all being part of the same massively parallel, "all of the above" effort to revitalize democracy, it's possible to identify seven key goals:

- Cultivating compromise. Democracy doesn't work if parties don't compromise. If one or both sides are unwilling to compromise, given the relatively equal distribution of power between the two sides in America's two-party political system, this is certain to result in continued hyper-polarized conflict (even though, at any given time, one side may dominate).

- Cultivating respect for all identity groups. One of the interesting opportunities for change is based on the fact that many of today’s political struggles revolve less around interests, and more around identity. People are afraid to compromise because they feel compromise is selling out “their tribe.” But while identity is not compromisable, it is also not win-lose. Rather, it is win-win. The more one side feels secure in its identity, the less it will feel a need to attack the other side’s identity. So, one key to a healthy democracy is developing a healthy respect for the many identity groups to which its citizens belong and forsaking efforts to place those groups in some sort of hierarchical order of superiority.

- Promote Reconciliation. Promoting compromise and respecting identity groups paves the way toward reconciliation, which John Paul Lederach defined as the "meeting place" between truth, justice, mercy, and peace. Healthy democracies promote both retrospective reconciliation, through which the truth is found out about the past, and justice is done, in combination with mercy, to obtain peace, and prospective reconciliation, where all the different groups work together to figure out a way to live together in relative harmony going forward.

- Effective Communication and Problem-Solving. Leaders and grassroots citizens must be able to understand the nature of the problems they face; the concerns, interests, and needs of all stakeholder groups (not just their own); and the advantages and disadvantages of options for addressing those problems, concerns, interests, and needs. Without that, effective problem-solving becomes very difficult, if not impossible.

- Preserve Electoral Integrity and Continuity. Although democracy involves much more than elections, free and fair elections and acceptance of election outcomes, even when one loses is essential to a functioning democracy. In healthy democracies, people must feel that, even if they lose one election and the winners enact policies that they (the losers) find unacceptable, they (the losing side) can regroup and try again in the following election. They also need to know that they still have inalienable rights that the tyranny of the majority can't take away. If people fear that losing one election or one decision will make it impossible for them to uphold their values or meet their needs forever, they will fight as hard as they can to win – even by cheating or using violence or other destructive strategies in an all-out effort to prevail.

- Expose and Delegitimize “Bad-Faith Actors.” Another key to a successful democracy is its ability to discredit, and to the extent possible block, the actions of “bad-faith actors” — people who refuse to engage in good-faith efforts to make democracy work, and instead, they try to subvert or destroy democratic institutions and processes to advance their own selfish goals

- Limit Massively Parallel Partisanship. The Achilles Heel of this whole approach is the fact that massively parallel processes for organizing complex systems can also function in ways that continue to drive the hyper-polarization spiral. Right now, in the United States, most people are, indeed, working roughly toward the same goal. But it is not any of the goals listed above. Rather it is the goal of decisively defeating “the other side,” “the enemy.” The result is massively parallel hyper-polarization, or as we have called it elsewhere, “massively parallel partisanship.” Escaping from this dynamic requires the "great reframing" that we talked about in the first newsletter of this series — a reframing in which people come to realize that the principal threat they face is not each other, but rather, the hyper-polarization dynamics that are destroying the democratic institutions that everyone relies on to protect their interests.

Massively Parallel Democracy Building/Civic Renewal Roles

So far we have identified over fifty roles that need to be played by people seeking to strengthen democracy and/or civic engagement. We divide these roles into two categories: conflict strategists and conflict actors, drawing on the distinction between "left brain" and "right brain" thinking.

Strategic roles are “left brain” roles — the people who figure out what needs to be done. They include people who are trying to look at the big picture, figure out what is going wrong, and what, in principle, can be done to fix those problems.

Action roles are the “right brain” roles played by people who are actually “on the ground,” doing the work of implementing the fixes suggested by strategists. They tend to be more narrowly focused, both in terms of the location of their work, and the nature of the activities they undertake. The first category of conflict actor we list is "grassroots citizens" — people who conscientiously exercise their civic responsibilities, while also supporting the larger democratic system and people working in the many other massively parallel roles. They do not have special training; they are not playing one of the other roles. They are just engaging responsibly in their role of “citizen” and taking that role seriously, realizing that it not only entails rights, but also responsibilities.

Both groups are essential and complement one another. (In practice, of course, many people can simultaneously act as strategists and actors – this is what “reflective practice” is all about.)

We don't have room to explain what each of the roles is here, but you can read about them in the roles section of the Guide and see an overview on the two charts below. (If the charts are too hard to read, click on the diagram (not the heading), and they will open up bigger in a separate window. The heading links to the Guide sections on Strategists and Actors.

MP Strategy Roles

MP Actor Roles

Please Contribute Your Ideas To This Discussion!

In order to prevent bots, spammers, and other malicious content, we are asking contributors to send their contributions to us directly. If your idea is short, with simple formatting, you can put it directly in the contact box. However, the contact form does not allow attachments. So if you are contributing a longer article, with formatting beyond simple paragraphs, just send us a note using the contact box, and we'll respond via an email to which you can reply with your attachment. This is a bit of a hassle, we know, but it has kept our site (and our inbox) clean. And if you are wondering, we do publish essays that disagree with or are critical of us. We want a robust exchange of views.

About the MBI Newsletters

Two or three times a week, Guy and Heidi Burgess, the BI Directors, share some of our thoughts on political hyper-polarization and related topics. We also share essays from our colleagues and other contributors, and every week or so, we devote one newsletter to annotated links to outside readings that we found particularly useful relating to U.S. hyper-polarization, threats to peace (and actual violence) in other countries, and related topics of interest. Each Newsletter is posted on BI, and sent out by email through Substack to subscribers. You can sign up to receive your copy here and find the latest newsletter here or on our BI Newsletter page, which also provides access to all the past newsletters, going back to 2017.

NOTE! If you signed up for this Newsletter and don't see it in your inbox, it might be going to one of your other emails folder (such as promotions, social, or spam). Check there or search for beyondintractability@substack.com and if you still can't find it, first go to our Substack help page, and if that doesn't help, please contact us.

If you like what you read here, please ....