Genocide

By

Chris McMorran

Norman Schultz

August 2003

|

|

See also the ICGLR/Beyond Intractability Genocide Prevention Knowledge Base with an extensive set of articles on

Materials Organized by Task

|

Genocide Defined

Genocide is generally defined as the intentional extermination of a specific ethnic, racial, or religious group. Compared with war crimes and crimes against humanity, genocide is generally regarded as the most offensive crime. At worst, genocide pits neighbor against neighbor, or even husband against wife. Unlike war, where the attack is general and the object is often the control of a geographical or political region, genocide attacks an individual's identity, and the object is control -- or complete elimination -- of a group of people.

The history of genocide in the 20th century includes:

- the 1915 genocide of Armenians by Turks;

- the attempted extermination of European Jews by Nazis during World War II;

- the widespread genocide in Cambodia during the 1970s;

- the "ethnic cleansing"[1] in Kosovo by Serbs during the 1990s;

- the killing of Tutsis by Rwandan Hutus in 1994.[2]

Since 1948, the United Nations has defined genocide as "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such."[3] Actions included in this definition are:

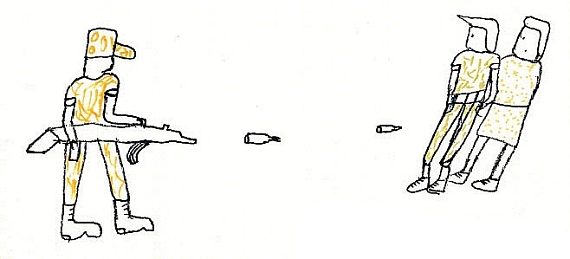

- Killing members of a group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of a group;

- Deliberately inflicting on a group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within a group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Notice that in the U.N. definition, murder is not the only way to destroy a group. For example, the recent Australian practice of forcibly removing biracial Aborigine children from their parents could be classified as genocide, since the goal of this practice was to assimilate the children into mainstream Australian culture, and thus slowly erode the Aborigine culture and population.[4]

|

Causes of Genocide

The underlying causes of conflicts that result in acts of genocide often have deep historical roots. Stereotypes and prejudices can develop over centuries. Ethnic and cultural distinctions often result in the formation of "in-group" and "out-group" thinking, where members of different races, religions, or cultures view each other as separate, alien, and "different." Identity groups are formed from such thinking.

In many regions, members of different identity groups, for mutual advantage, develop conflict prevention methods. Yet where resources are limited, or where pressures are placed on societies because of political or economic instability, relations may degrade. This can lead one group to become convinced that many of its problems are the fault of another group, and that all of those problems would be resolved if only the other group no longer existed. Guy Burgess has named this irrational and potentially dangerous idea the "into-the-sea" frame. Coexistence and power sharing are not considered to be viable options, and the more powerful group instead desires to exterminate the other (i.e., drive the other side "into the sea"). Often there is a "coherent and vicious elite" led by a majority-supported dictator who incites genocidal movements. Such movements find expression more readily when powerful political entities are made up of a common ethnicity and when minorities are marginalized.

| "Can I see another's woe, and not be in sorrow too? Can I see another's grief, and not seek for kind relief?" -- William Blake |

Responding to Acts of Genocide

Genocide, like any morally relevant action, can be supported, denounced, or viewed with apathy. One's moral convictions will result in varying responses to genocidal acts. Perpetrators of genocide often feel completely justified in their actions, and may draw on local cultural or political values to curry favor. This can lead to a response of support, thereby furthering the criminal acts. Others, while not participating in the acts directly, may support them by financial or political means.

Still other groups may attempt to take a neutral, apathetic stance. International law and historical precedent, however, has made it extremely dangerous for relevant parties to attempt to merely stand by. An example of such behavior was the Swiss policy of neutrality in World War II.. In the mid-1990s Swiss banks were held accountable for servicing the financial interests of Nazi party members and for failing to settle accounts with Holocaust victims or their surviving family members. It would seem that parties that are in a position to oppose acts of genocide, but fail to do so, can expect punitive repercussions.

The international community, following international law, sometimes attempts to stop genocide before it happens, or while it is in process. Often, however, the ability to do anything effective is minimal. Another approach is punishment after-the-fact, which is supposed to not only extract retribution or justice, but also act as a deterrent against future genocidal acts. Whether the deterrence effect is real, however, is unclear.

Preventing acts of genocide has become an important topic in peace research. Preventing genocide implies understanding how genocidal motivations begin and how groups become powerful enough to impose their plans on their victims. This involves the ability to recognize how ethnic and political values mesh in potentially dangerous ways and how elite organizers of genocide obtain state power. In addition to developing working theories of how genocidal acts begin and progress, prevention also necessitates the ability to detect signs of genocidal schemes and respond to them as early as possible. Government investigation agencies (such as the FBI and Interpol), the United Nations, and independent human rights organizations (such as Amnesty International), utilize some early detection methods. Attempts to prevent genocide usually involve preventive diplomacy and violence prevention. Dealt with elsewhere in depth, suffice it to say here that this involves both Track I and Track II diplomatic efforts to diffuse tensions and try to encourage the parties to negotiate at least a settlement, if not a resolution of their differences -- enough to prevent widespread violence.

Sanctions are also sometimes used as deterrents or punishments for unacceptable behavior. For example, economic, financial and military sanctions were imposed against the Yugoslav Federation to try to end their support of the Serb's "ethnic cleansing," a euphemism for genocide. Military intervention may also be called upon, as was the case with U.N. peacekeeping forces and later NATO forces acting in Bosnia in the 1990s.

International law also supports after-the-fact prosecution of war criminals. International law was the force behind the Nuremberg trials of Nazi officers in the late 1940's and, in more modern times, the trial of former Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milosavic at The Hague. The International Criminal Court (ICC), established in 2002, is intended to make such prosecution more effective. Though adherence to the ICC Statute (the Rome Statute) varies from country to country,[5] 139 countries signed the initial statute and the 60-country ratification minimum required for the ICC to enter into force was reached on April 11, 2002. Both the United States and Russia have refused to accept the jurisdiction of the ICC, however, leading to questions about how effective the court can be without their participation.

Problems with Punishment

In actuality, all forms of punishment face difficult challenges. Many question the effectiveness, and the ethicality, of economic sanctions, especially since sanctions can easily affect an entire nation's economy, arguably punishing innocent citizens for the crimes of their government or of a powerful faction. Legal punishment for genocidal acts can be frustrated by an inability to find the individuals responsible. Also complicating the matter is the fact that the number of people who committed the crimes is often so large as to make a trial huge, costly, and impractical. Military action also presents the challenges of how to engage, when to intervene, and how long to stay when hostilities have subsided, in addition to the delay from the time when military action is deemed necessary and when (if at all) it is approved by the international community.

Threat of punishment can also prolong a conflict. If one side fears prosecution if they end the conflict, they may continue, even though they realize that they cannot win. One answer to this fear is offering amnesty to all sides, as was done in South Africa with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Here the belief was that reconciliation and stability would be much more easy to achieve if people testified about their heinous actions, but then were forgiven, instead of prosecuted. This, many argue, has allowed that intractable conflict to be transformed much more effectively than it might have been, had whites been threatened with prosecution for crimes against humanity or other violations of international law.

The Aftermath of Genocide

Acts of genocide cause people to flee dangerous areas, becoming refugees or internally displaced people (IDPs). Great numbers of refugees fleeing to neighboring countries can be a social, political, and economic burden on those countries. Refugees often encounter discrimination in new countries, and may have no choice but to live in refugee camps, not knowing when or if they will return home. When they do return, they don't know if they will find their homes and possessions intact. This is but one of myriad problems faced by individuals, communities, and societies after a genocide ends.

Once the acts of genocide come under control, and accountability for the crimes is being enforced, the processes of peacebuilding, reconciliation, and healing must begin. Victim groups will, understandably, have a great deal of hatred for their oppressors. Relations between enemy ethnic groups must improve; otherwise retaliatory violence is essentially assured. Efforts to forge new relations between groups and to empower the victim group are justified. Realistically, though, true reconciliation will likely take a long time, as the crimes are horrible enough to make them nearly unforgivable.

The greatest challenge following genocide is rebuilding a society, since a conflict that at one time might have been resolved may now have become intractable. The rebuilt society must have a power-sharing form of government in order to prevent future inequalities that could lead to violent retaliation. Preventing a cycle of hatred and violence becomes the central challenge.

However, sharing power with one's past enemy, especially following such a horrible crime as genocide, may not be possible. Peace is often tenuous in these situations, as is the case today in Rwanda and Cambodia .

[1] Ethnic cleansing is a euphemism for genocide. Ethnic cleansing means "the purging, by mass expulsion or killing, of one ethnic or religious group by another" according to the Oxford English Dictionary "ethnic cleansing" avaliable at http://www.oed.com/. The term is derived from the Serbian and Croatian etniko ienje and was first used in the 1990s in the former Yugoslavia, especially to describe the actions taken by the Serbian government against ethnic Albanian Muslims living in Kosovo. The Serb government wished to have a Serbia for Serbs and tried to rid its southern region, Kosovo, of non-Serbs.

[2] Some moderate Hutus were also victims of mass killings in 1994.

[3] United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

[4] Decoust, MichPle. "Australia 's Forgotten Dreamtime." [on-line] (Le Monde diplomatique, October 2000) Available from http://mondediplo.com/2000/10/14abos. Accessed 28 January 2002.

[5] Notably, the United States and China have not ratified the Rome Statute, each having political objections to certain aspects of the treaty. Negotiation efforts between the ICC and countries yet to ratify its power continue. For up-to-date information on such efforts, see http://www.iccnow.org/countryinfo.html

Use the following to cite this article:

McMorran, Chris and Norman Schultz. "Genocide ." Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: August 2003 <http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/war-crimes-genocide>.