Review of Peter Coleman's The Way Out

by Heidi Burgess

January 19, 2022

| In early fall, 2021, Columbia University sent me a review copy of Peter Coleman’s recent book, The Way Out: How to Overcome Toxic Polarization, with the hopes that I would write a review or otherwise comment on the book on this blog. (I didn’t realize they were expecting that at the time; I thought they were hoping that I would use the book in one of my courses.) Shortly thereafter, the Negotiation Journal (NJ) also asked me to review the book, and I said “yes” to them. When I realized I’d unknowingly promised reviews to two different entities, I asked the Negotiation Journal editor if it would be okay if I wrote a short version of my NJ review here, encouraging people to read the longer review in the journal. That review, it turns out, was published online on November 23, 2021—I didn’t realize that at the time—and will be coming out in print, I believe, later in January. So here is the shorter, “teaser” review and I hope you will look up the NJ review as well. Further note: On Feb. 1, I discovered that Wiley (the publisher of the NJ) gives authors a "sharable link" which allows us to share a read-only copy of the article to an unlimited number of people, even posting it on their personal webpages. Since Guy and I are authors of this blog, I am hoping this will be considered our personal webpage, and am sharing that link here: Sharable Link to NJ review. |

In the preface to The Way Out, Peter Coleman writes:

There is an old tale about a Cherokee elder who was teaching his grandchild about life and said “A fight is going on inside you. It is a terrible fight between two wolves. One wolf represents fear, anger, envy, greed, arrogance, and ego. The other stands for joy, peace, love, hope, kindness, generosity, and faith. The same fight going on inside you is inside every other person too.” The child thought about it for a moment and then asked, “Which one will win?” The old man replied, “The one you feed.” (x)

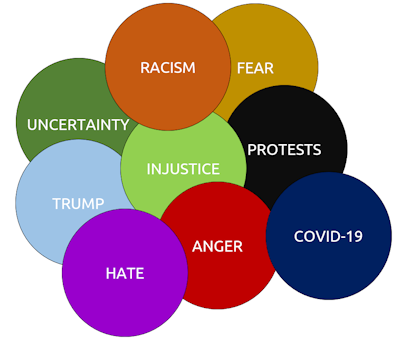

I love that metaphor, so I am repeating it here with the same observation I made in the NJ: right now, in the U.S. and in many other places around the world, “the first wolf is not only wining, it has a commanding lead in this contest.”

In The Way Out, Coleman does an excellent job of explaining why the wolf of anger and fear is is winning so handily, but he does a much poorer job, in my opinion, of delineating a credible “way out” of our mess. I don’t want to repeat everything I said in the longer review, as I hope people will go to the Negotiation Journal to read it there (right now, at least, it is available for free on the Journal’s home page, but that will likely change soon, so go quickly!) But for an introduction, I’ll cover some of my key points here.

| Why is the wolf of anger and fear winning? It is because we can't deal with the complexity of our socio-economic and political problems in a constructive way. We over-simplify our narratives into us-versus-them explanations of the problem and we use overly simplistic solutions to try to address complex issues. |

First, why is the wolf of anger and fear winning? Coleman suggests that two highly interrelated things are making people angry, fearful, and arrogant. One is the nature of current social, political, and economic systems, which are extremely complex, linked with human's general dislike of and inability to deal effectively with complexity. Coleman explains that we all tend to simplify our understanding of the world by creating a simple good-guys/bad-guys narrative. Everything our group believes and does is good, everything the other guys believe and do is bad (or even evil.) And when anybody tries to fix this problem, they tend to do so as if the problem were complicated, not complex.

That's a distinction that systems theorists make that is obscure to most people, but it is very important, and is a key point Coleman makes throughout his book. Complicated systems (which Coleman refers to as "clock problems") have lots of pieces or parts, each of which is connected to the others in established and predictable ways. Complex adaptive systems, (which Coleman refers to as "cloud problems") also have many pieces, but those are not connected to each other in established or predictable ways. Rather, each “piece” has its own “decision rules,” and will act in ways that will affect other parts of the system in unpredictable ways.

| Complicated problems can be fixed by fixing broken pieces. Complex problems cannot be remedied in that way. |

Complicated systems (or clock problems) can be fixed by identifying the broken part, replacing it, and putting it back in where it belongs. Complex adaptive systems (“cloud problems”)cannot be “fixed” that way. We don't have a blueprint or plans. We don't know what all the parts are, or how they relate to each other. We don't know if we push in one place, where that push will be felt through the system. So we cannot design a whole-system response which will “fix” the system in the same way we can fix a clock.

A second contributor to the “bad wolf” winning is the tendency of complex systems to self-organize around what Coleman and complexity theorists call “attractors.” Attractors, Coleman explains, “are strong, complicated change-resistant patterns” exhibited by systems. I like to think of attractors as black holes—they have strong forces that pull people in, and then it is very difficult, if not impossible, to get out. An example of an attractor is the continuing standoff between Democrats and Republicans over the events of January 6, 2021. Right after January 6, a good number of Republicans denounced the people who attacked the Capitol and Trump’s role in encouraging that attack. But soon, almost all of these Republicans fell back into line with Trump’s narrative that the election was stolen, and January 6 was a legitimate protest of that fact. The Republican/Democratic standoff attractor was pulling them back into the fold.

| Both Republicans and Democrats are caught in the same attractor that is locking them into perpetual battle over the 2020 election. That battle is making compromise on that issue and all other issues impossible. |

That narrative—that the election was stolen—is still driving Republican efforts to stack state legislatures and electoral offices with Republican operatives, to make sure that they prevail in upcoming elections. Democrats, meanwhile, are pursuing lengthy hearings on the January 6 events, in the hopes of discrediting and disempowering the political machine that allowed that to happen. In reality, this is all being driven by the same attractor, which has both sides locked in perpetual deep, hateful, and fearful opposition. No one is contemplating compromise or finding “a way out,” despite the increasing number of warnings about a coming civil war. The attractor is so powerful that the only solution most see to such threats is winning the war, not finding a peaceful way to avoid it.

A few people, however, are beginning to try to develop and sell ideas about how to avoid such an outcome, and Coleman, of course, presents his answer(s) in this book. Unfortunately, however, that is where the book, in my view, falls short. As he did in his earlier book, The Five Percent, Coleman lays out a series of steps we need to take to find our "way out." These include (1) “think different,” (2) reset, (3) bolster and break, (4) complicate, (5) move, and (6) adapt. While such lists appeal to readers because they are easy to understand, there are not a particular set of steps that will fix any complex adaptive system. Laying out steps is "complicated thinking," not "complex thinking." In addition, when you look at the details of each of these steps, their likely efficacy is not convincing, at least not to me, although some of his suggestions did resonate:

| We should look at "the nature of the context that gives rise to these conflicts" and "work with the flow of forces within the context to support the rise of more constructive patterns. |

(1) Think different. (Coleman explains this isn't a typo, but rather a term he copied from Apple describing how their designers were better than the competition.) This is one of his suggestions that I agree with, as he says that we have to stop thinking in terms of clock problems and start thinking of cloud problems. Instead of focusing on broken pieces of the conflict in order to fix them, we should look at "the nature of the context that gives rise to these conflicts" and "work with the flow of forces within the context to support the rise of more constructive patterns." (73) This is true.

(2) Reset. Here's one of the places I find his suggestions lacking. He says, even before he lays out his steps, that three things (taken together) make attractors open to change. The first is instability--something must throw the system "out of whack." Second, there must be a mutually-hurting stalemate in which neither side can win, and thirdly, there must be a "way out." Both in this discussion and in the Reset chapter, he asserts that Trump's election, and then COVID were sources of instability that threw our social and political systems "out of whack." He correctly observes that we are in a hurting stalemate, so he suggests that all we need is his book to provide the way out. But neither Trump's election, nor COVID have weakened the attractor of polarization. Rather, both have strengthened it substantially.

(3) Bolster and Break. Coleman tells us to bolster positive aspects of our relationships and break negative aspects thereof. Here he suggests that we try to strengthen positive aspects of our relationship that used to exist (and maybe still do in background), but are overpowered by destructive aspects of our relationships. For instance, before our current era of hyper-polarization, people used to have positive relationships people on the other side. We need to look for those long-forgotten positive thoughts and try to strengthen them, he asserts.

(4) Complicate--Embrace Contradictory Complexity. Coleman starts by making a distinction between "consistent complexity" which is a positive feedback system in which many factors align and reinforce each other (hence forming an attractor) and "contradictory complexity" which is a negative feedback system of checks and balances which is de-escalating and de-polarizing instead of the opposite. He suggests we embrace contradictory complexity by acknowledging our own doubts and contradictions.

(5) Move. Here Coleman is referring to both physical and psychological movement. He argues that we can better open up our thinking by walking around outside. Guy would agree, as he writes by going for hikes and dictating, but I'm not sure this is a scalable approach. Coleman suggests we can create psychological movement with "forward framing." As I explained in the NJ, "Instead of focusing on grievances, frustrations, and current problems, as most conflict resolution processes do, he suggests starting by brainstorming, asking “where you all ideally want to go” (170).

| Create psychological movement with forward framing, or what Ebrahim Rasool described as "starting from the end." We must recognize, as they did in South Africa, that America belongs to all who live here, and make a comfortable place for everyone--conservatives and progressives. |

This is consistent with the suggestions I have made in my video and article on Prospective Reconciliation in which I argue for "starting with the end." This is an idea I learned from Ebrahim Rasool, former South African Ambassador to the U.S.. Rasool explained that South Africa was able to emerge from the apartheid era peacefully by starting with an image of the South Africa they wanted to attain, one in which "South Africa belonged to all who lived there." If we want to emerge from hyper-polarization, we too, need to identify what we want the United States to be like. If we want it to be a haven for Progressives with no place for Conservatives, we are not going to have a peaceful country. Likewise, if we want it to be a haven for far-right, white-supremacist, fundamentalist Christians, with no room for Progressives, we won't have a peaceful country. If we want a peaceful country, we need to agree that America belongs to all who live here, and we need to figure out how to live in peace with people who are very different from ourselves.

(6) Adapt. Here again, Coleman argues that we get into trouble when we treat "cloud problems" as if they were "clock problems," and to help us avoid this he suggests five "complex adaptive competencies". These include tolerating ambiguity, fostering cognitive, integrative, emotional, and behavioral complexity, and considering future consequences for our actions. These are all good suggestions, as they are all designed to get us out of our overly simplistic, knee-jerk, us-versus-them, right-versus-wrong thinking. But these are all things that are difficult for individuals to do, and immensely difficult for enough individuals to do to make meaningful changes in a complex social and political system as large as the United States (or even a much smaller country).

| Coleman's suggestions are good for people operating at the individual or small group level. Now we need to figure out how to scale them up to the societal level. |

I discuss many more of Coleman's specific suggestions in the longer review, concluding that many of them are good suggestions for people operating at the individual or small group level--indeed, they echo many suggestions we make in various parts of Beyond Intractability, and are consistent with traditional conflict resolution training.

The big disconnect for me is how these suggestions can be scaled up to provide a "way out" for our whole society. How are enough people going to be in a position to undertake his suggestions, and have the skills and willingness to do so all while bad-faith actors are working overtime to prevent all such efforts from being successful? The hyper-polarization attractor is much stronger and is working much faster, it seems to me, than individual efforts to work against it. We need a much more systemic-level response, I believe, if we are actually going to find "a way out."

This is not arguing for structural change instead of individual change (although many structural changes will no doubt be needed). Rather, we are calling for a society-wide, multi-faceted response such as the kind we have laid out in our article on Massively Parallel Peacebuilding.

| We are going to need a massively parallel response by thousands or millions of people if we are going to be able to find a real way out. |

Now I don't think we are all that much closer to "the answer," than Coleman is, but I do think that it is going to take a massively parallel response of some kind, made by tens of thousands, if not millions of individuals and organizations, if we are really going to be able to overcome the attractor of hyper-polarization before it swallows us up and destroys us entirely.