Carrie Menkel-Meadow: Words Matter!

“These are times that try men’s (sic, women’s too!) souls.” Thomas Paine, The Crisis

“Black Lives Matter”

“All Lives Matter”

“Kung/Chinese flu”

“Fake News”

Blue/Red

Black/White

“Wear a Mask”

“It’s all a hoax!”

“Defund the Police”

“Can’t we all just get along”[2]

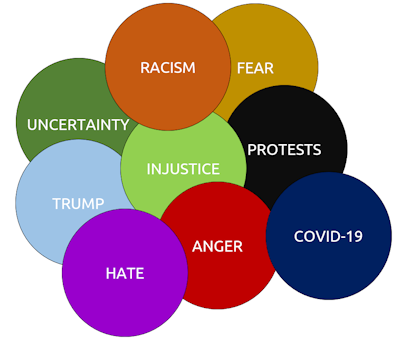

We hurl words around –weaponized—to both claim affinity and for organizing, but also to demarcate, to separate—more than physical or social distancing—political distancing, which turns into real human distancing. Using words as images, memes, and short cuts we simplify to have stand-ins for deeper thinking, more complex meanings, to call attention to our identities, allegiances and values, and I would argue, sometimes to avoid the greater complexity we find in life, value differences and policy solutions.

In our complicated times of COVID-19 and increased activism around racial injustice, it might be important to step back and consider how slogans both help and hurt us and to think about how we, as conflict resolution professionals, might “reframe” and recraft some words for concepts that are more likely to word-paint with more inclusive, rather than dividing, words and to spur our thinking for more protean and creative possible ideas for solutions.

Don’t get me wrong—I am a former civil rights lawyer, anti-war activist and early feminist who marched in the 1960’s, 70’s, 80’s, 90s and early 2000’s, and more recently (think: “We won’t go back,”, “Hell, no, we won’t go”, “Hey, Hey, LBJ, how many people did you kill today?”, “Get your laws out of our uterus”). But think also “I have a dream,” “We shall overcome”, “Make love, not war,” “Equality for all,” “Women’s rights are human rights.” What power words have to bring people together over deeply-felt values and commitments, for chanting, for calls to action! But these words are also used to divide.

| Words become talismans for use in creating the kinds of “tribal” loyalties that inspire political action, as well as voting behavior and everyday interactions. |

Linguistics experts, political scientists and strategists like George Lakoff (Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind (1987); Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate, 2004); The Little Blue Book: The Essential Guide to Thinking and Talking Democratic (with Elisabeth Wehling, 2012), Frank Luntz, Words That Work: It’s Not What You Say, It’s What People Hear (2007) and many others, drawing on the work of advertisers (David Ogilvy, On Advertising, 1983) and psychologists (e.g. Cialdini’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, 1993) know that words become talismans for use in creating the kinds of “tribal” loyalties that inspire political action, as well as voting behavior and everyday interactions. Jonathan Haight, social psychologist, has suggested that we view the world through the prisms of the various “tribes” (religion, political affiliation, class, caste and color) to which we “belong” (The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (2012) and then confirm our views by living in our “bubbles”. Indeed, as we now “bubble” and “pod” with affinity groups during the COVID-19 period of quarantine and isolation, watching protests of the left and rallies of the right, we are likely to be increasing our sense of core values and allegiances and hostility to those with whom we disagree. Wearing a mask for public health has become a political symbol, rather than an act of mutual respect for our interdependence, as germs spread indiscriminately among us.

| The crafty wordsmiths of political campaigns and political culture (think “right to life” vs. “right to choose”—who is against life?) have been able to mobilize and separate with slogans, and sadly, to deeply affect democracy. |

The crafty wordsmiths of political campaigns and political culture (think “right to life” vs. “right to choose”—who is against life?) have been able to mobilize and separate with slogans, and sadly, to deeply affect democracy (Make America Great, Again?). Think of the cleverness of Republican strategists’ frames and phrases, “death tax,” “death panels,” “light switch tax,” “Contract with America,” “family values,” “axis of evil,” “silent majority,” “a thousand points of light,” “compassionate conservatism” and the upbeat message (and metaphor) of “morning in America” (conveying optimism by a man, Ronald Regan, who then did everything he could to tear down social welfare and government programs (“government is the problem, not the solution”) and intimidate (by large defense spending) our then largest global adversary. Today—‘the Chinese virus’—Kung Flu! As social scientists know, fear is one of the most powerful emotions to prey on by those promising action and “leadership.” But all of us should think back to our childhoods, what helped us conquer our fears? – More likely, it was a nurturing (if we were lucky enough to have them) parent who reassured us and took “care” of us, rather than someone who actually “killed” the monsters under the bed or in the closet with an evil eye or a fictional weapon.

| Now we face a crisis of wordsmithing and slogans on all sides of political discourse. |

Now we face a crisis of wordsmithing and slogans on all sides of political discourse—will it unify and affect change to completely “defund the police”? While “All Lives Matter” has become a symbol of failure to recognize the singular struggle of Black Americans, and now a politically incorrect statement, how might we use an inclusive phrase like “All lives matter, only when Black Lives Matter" to help us bring all people together to work on racial injustice? Is it the same to tear down a statue of George Washington (who, in fact, did free his slaves on his death, though it took a little more time to accomplish the feat), unlike Thomas Jefferson, who did not, Declaration of Independence author that he was), as Robert E. Lee and other confederate racists and war-losers? Whose monuments should stay (in the name of learning some history, see Caroline Randall Williams, “My Body is a Confederate Monument,” New York Times June 28, 2020, Opinion page 4) and whose should go as glorifying and honoring ignoble deeds (Confederates, King Leopold II of Belgium, Cecil Rhodes, others)? Monuments, like words unite, commemorate, compress ideas, and separate -- seldom telling enough of the true and whole story as the massive figures in metal simplify the images of what really happened.

| We need to own the complexity of the issues we now face and use our professional skills to really “reframe” not just the words, but the concepts and commitments we need to engage in really transformative thinking and acting. |

As one committed to mediational, joint-group problem solving, as well as political and social justice and change, and the kind of conflict resolution that stops the violence, but not the thinking, I think we need to own the complexity of the issues we now face and use our professional skills to really “reframe” not just the words, but the concepts and commitments we need to engage in really transformative thinking and acting. As Eliza Doolittle sang in My Fair Lady, “words, words, words, I am so sick of words, I get words all day through, first from him, and now from you, is that all your blighters can do?.....Show me now!” (Show Me! (Lerner & Lowe). At some point we need to do more than speak and scream and yell, whether eloquently or angrily. We need to “frame” the problems realistically and motivationally and then try to engage seriously with what we can do to 1) stop the violence 2) change the narrative and 3) come up with some workable possible “solutions” (in my book, always contingent, as we learn more and conditions change).

The word used in modern Hebrew to connote mediation is “gishur”—to bridge. We need to find words, concepts and projects (tasks) that can bridge at least some (never all) of our differences to word paint and act for inclusion, collaboration and diversity of ideas (not just ethnicity or demographics). What we mediators do is to ask people in conflict to try to see the world from other perspectives, to hear stories of actual experiences, to move to some empathy, if not total agreement, and then to see how we could work to make a better situation—sometimes only lemonade out of lemons, but that is a start (to perhaps lemon meringue pie to continue the metaphor, where there will be pie for all!).

| We must look at and feel the pain of what has happened before, to us, to our forebears, and to get either apologies, or justice (formal legal or personal and social) and understanding before any “move” to the future can make sense. |

I have never been a mediator to say “Let’s not focus on the past, let’s look to the future.[3] We must look at, feel the pain of what has happened before, to us, to our forebears, and to get either apologies, or justice (formal legal or personal and social) and understanding before any “move” to the future can make sense. As a child of Holocaust surviving parents and grandparents, I lived with daily stories of the cruel acts of the Nazis, but my parents, in dealing with my nightmares, inspired by their true stories, taught me to do something about the injustice still around us then (in my youth, nuclear proliferation and civil rights) and we worked in a diverse, secular and cosmopolitan religion of Ethical Culture, with the parents and children of racial, ethnic and religious inter-marriage. As a young adult I learned anthropology from Margaret Mead—all cultures are different and almost all of them have goods and bads, from which we can learn to possibly restructure our own societies. So we must “deal” with the past (Juneteenth as a national “commemoration”, not a holiday?, as Julani Cobb reminds us (“How Freedom Came,” New Yorker, June 29, 2020). We must prosecute police who murder, repeatedly, black men and women and children, but we must also make sure that there is public safety, and security for all. Rather than “defund” or eliminate things, shouldn’t we be adding, spreading equitably what some, but not all, have? Are “Redo” Redesign” “Remake” yes, even “Reform” (re-form!), rather than “de-fund,” slogans we can all get behind? Shouldn’t we be talking about “Re-funding” Social Services when that is what we want? We want de-militarized police, community safety and appropriate non-violent resolution of some situations.

As Democratic (party) strategists now seek new “brands,” memes and slogans to defeat the inhumane man who lives in the White House, (Joseph O’Neill, Brand New Dems, New York Review of Books, (April 29, 2020), they suggest we try to capitalize on what Democrats care about—care (Affordable Care Act), fairness, trust, more concretely, health caring, affordable housing, employment rights, social legislation, science, expertise (competence, anyone?), family (defined more broadly and inclusively to include families other than conventional nuclear or biological families), equity, equality, opportunity, global interconnectedness, climate change amelioration, and the participation of all people in the rules that affect them (that is what the ’68 Democratic convention was all about!), with mutual respect, and indeed celebration of differences, rather than adherence to a uniform code (Trumpism??) of corporate domination and religious conformity.

| We need participation in "small d" democracy to develop words, ideas and actions to navigate our troubled waters. |

Whether the Democrats with a large “D” succeed or not (of course, I hope they do!), I am more concerned at the moment with our small “d” democracy and the participation we need to develop words, ideas and actions to navigate our troubled waters. In 1993 when I heard Hillary Clinton speaking about an earlier effort to provide health care in the United States, she talked about interdependence of human beings. At the time she used examples of recurring tuberculosis (in interactions on public transportation or in the cross-class contacts of workers and the more affluent employers, and students in all kinds of schools), or sadly, differentiated health outcomes based on wealth, (diagnosis and treatments of cancers, meningitis) and race and ethnicity. How ironic it is to me now, that in this pandemic, her word of “interdependence” seems so essential to our wellbeing, even as we isolate. My brother is a critical care doctor in the Bronx. He saw early on, before widely reported, the death toll (more than a “tax’!) visited differentially on color, “pre-existing conditions,” class, and access to hospitals and ventilators. We watched as several hospitals and their committed staffs were featured on documentaries, as New Yorkers banged pots at night for appreciation for first responders (fire, ambulance, and yes, some police), and health care workers. Spike Lee commemorated the emptiness of one of the world’s most active and diverse cities with a short film that demonstrated what New York looked like without its people. For the most part, in early days, many of us, not all (see rising rates of infection in non-compliant states), saw our interdependence, when we could, and wore masks and curtailed our human interaction for the greater human good.

But when George Floyd was killed with a knee to his neck (literally, after so many years of “get your foot off my neck” as the long metaphorical, and real, battle cry of Blacks and women), many took to the streets to demonstrate another form of interdependence—we cannot stand aside when injustice continues for so many years. “We” must stand up for all and show the world we are willing to risk our health. (Consider, as mediators, that this feeling of commitment to that cause of justice is mirrored on “the other side” by those who risked their lives to attend Trump rallies. Not equivalent for sure, but consider, the irony of the similarity of motivation. (More horrible words—a tee-shirt seen at the Oklahoma rally on June 20,2020—Liberty, Guns, Beer and Trump! (LGBT). We put our firmly held values and beliefs above our own and other’s health!

So what can we do to “reframe” the word-paintings, perhaps to draw circles of inclusion, rather than the rough edges of rectangles and straight lines that demark too brittlely our differences?

Is it possible to craft new words and ideas that will also lead us to more engagement and better ideas?

Here are a few thoughts:

We are all interdependent! |

1. How about "We are all interdependent!" We need each other. Germs jump from person to person. All of us want to live and flourish, so we need to figure out how to do it together. I teach international law—our evil leaders may try to close borders, but this virus knows how to jump them! This flies somewhat in the face of American individualism and exceptionalism, but guess what, we are not so exceptional and we need others to survive.

| We have to learn to trust each other — and science, facts, and data too! |

2. To do that we have to learn to trust each other (and how about, science, facts and data too!). What are the conditions in which trust is developed, earned and kept (as well as lost)? And how do we treat each other “fairly” – a very complicated philosophical concept, but deeply felt by every ordinary human being.

| But rational data is not enough. We need to empathize and feel with (the original translation of empathy) others—even those outside of our kinship “tribes”, nations or other affiliations. |

3. But rational data is not enough, as I have often written, we need to empathize and feel with (the original translation of empathy) others—even those outside of our kinship “tribes”, nations or other affiliations. I am not a religious person (feminism is my religion, along with what Ethical Culture meant to me as a child) but I am a spiritual one—we are on this earth together, through viruses, hurricanes, tsunamis, cyclones, earthquakes and fires, as well as sunrises and sunsets—and we need to feel some connection to others to solve or at least survive these crises. We need science, but we need faith, that we can help each other in hard times and that people can get better and improve themselves, both for themselves and for future generations. How about “We are ALL In IT together,” even if we go out alone. If rational argument does not work, we have learned, feeling the pain of others can move us (not walking a mile in someone else’s shoes, but doing it with their, not your, feet!). What can we do to help very different people understand the world from other people’s experiences (guided mediation, travel, films, books, music) and most importantly, daily interaction with people who are different, but also human.

| Who doesn't need others? How can we encourage productive “bringing togetherness” (especially in the complicated “time of COVID”)? |

4. How can we encourage productive “bringing togetherness” (especially in the complicated “time of COVID”)? We are all vulnerable, at birth, near death and often in between. Who doesn’t need others? (That’s why I teach negotiation—how do we work with others to get what we and they need.)

5. Should we emphasize our common humanity—we are all temporarily on Earth—all of us need a “safety net”? (Who wouldn’t want one?) That’s why one Presidential candidate had to offer a “lock box” for social security. What new words and concepts do we need to convey that all are entitled, through their very humanness, to an opportunity to reach their full capabilities (thank you, Amartya Sen!)? Yes, ALL LIVES MATTER AND ALL LIVES MATTER ONLY WHEN EVERY SINGLE LIFE MATTERS! (whoops, I refuse to engage here with the question of what “life” is for this purpose—animals, fetuses, wait your turn, I am now talking to those of us who are already here, dealing with enough issues). This is basic HUMAN RIGHTS.

| How are we going to talk to each other, across histories, party lines, religious lines, gender lines and color and class lines? It is not so easy. |

6. What kinds of ways can we talk to each other productively? We need protests—let’s get your attention on this problem, finally!!!, We also need institutions to make things happen—alas, extreme polarization now has broken our political institutions. Where are the successful slogans and programs of yore—The New Deal, The War on Poverty? (Ok, the Green New Deal is trying to get some traction). Whether you think it is a red/blue, right/wrong problem, I think it is a complexity problem. Solutions are not simple. 40 acres and a mule never happened—probably neither will full reparations for the harms of past slavery, still visited on the present and future. (Some of my family received some highly inadequate wiedergutmachung from the German government after the second world war; my father refused it).

So, we have to come up with some other things. How are we going to talk to each other, across histories, party lines, religious lines, gender lines and color and class lines? Not so easy. As many cities have hosted “group-reads,” and as many schools at all levels will now require anti-racism reading (see any bestseller list these days to know those who buy books are trying to learn (more) about racism and anti-racism) we should encourage (virtual until back in proximity) group dialogues and problem solving sessions (see Public Conversations, Essential Partners, The Living Room, for groups that help facilitate such gatherings) at all levels of society (old fashioned town halls anyone, more inclusive?), whether or not fed back to government policy makers or just for more human understanding and “cross-group” talk.(Remember, “Getting to Know You”(The King and I, Rogers and Hammerstein this time!) Or, for those of us old enough, watching Alex Hailey’s Roots (one of the first TV multi-episode series) to an almost fully gripped nation in shared media time, if not fully shared experience.

7. And then there is Listening, I mean really listening,,, the classic therapist mantra of “I see you, I hear you” (with appropriate finger and eye movements) has been often parodied, see e.g. Parenthood) but what if we really did have to paraphrase and actively listen with care all of the time? In the slower times of COVID now would be a good time to practice. For we professional mediators, the similar mantra is “what are you curious about, what you like to know more about,,,,,,,”(the other person, your situation, the facts, the arguments, the reasons, the feelings, the possible solutions)?

8. And let’s look at some more successful re-labeling or reconceptualizing—“marriage rights” (used to emphasize the family, love and commitment relationship, rather than who in particular was seeking it—marriage for all those who want it and are prepared to commit to it. This technique of “keeping the focus off the focus” ( not “gay” rights) but working on the tasks together (equality of marriage rights) may shift the frame to more acceptance and inclusion. (Yes, I know not a direct on advocacy approach favored by all!). All wordsmithing and political organizing will still have elements of contest. I am not suggesting reframing successfully will be easy, but it should come with full on discussion and contention over choices and meanings.

As we work on different concepts to change our wordpaint (yes, absolutely pun on “warpaint”!), how about a few concrete ideas to stretch those words to some action:

| What would it look like to change “police” to “safety” departments? |

1. What would it really look like to change “police” to “safety” departments—what would that look like? How do we work on that at local, state and national levels? (Hint: UN peacekeeping “Security Forces” have been a very mixed bag with peace-only, little enforcement mechanisms).

| How about a bi-partisan Monuments Commission? |

2. How about a Monuments Commission (bi-partisan—possible?), identifying, then consideration of moving offensive monuments to a special location—see Gorky Park in Moscow for “fallen heroes,” or the statue park in Budapest—go to the Museum of Oppressors (really!) to learn some history (see Sanford Levinson, Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies, 2018). To have open discussions about this would likely be difficult, but a true act of democracy and real civic education (and would challenge my own notions that we do have to deal with the past to move forward. As Faulkner said, the past is not even past (yet).

| How about keeping the concept but rebranding the name “affirmative action”? |

3. And how about keeping the concept and rebranding the name “affirmative action”? I long labored as a civil rights lawyer to defend affirmative action as a necessary remedy for the continuing “incidents and badges of slavery” but how that term got word-switched to “quota” and led to claims of “reverse discrimination” now requires us to reframe, rename and then re-use this necessary concept. You can’t erase the privilege of hundreds of years by “freeing” people, without 40 acres and a mule (and an education and a family), and then hope we are all competing in the same way for “equal opportunity.” There is neither equality, nor real opportunity there. We need to do a “do-over” and “re-think” here. What do we call it “fair opportunity” ? What is really fair opportunity—sit with that one for a while… What is “fair” in our competitive society, with its grossly unequal endowments and privileges?

| How do we get REAL representation? |

4. And what about real “representation”? I merely reference the complexity of the Voting Rights issues here. In the early days of feminism, several commentators (thank you Mary Becker) suggested that every political district should have one male and one female representative (better representation of the genders, then essentialized, yes), not only to be “seen” but also to generate different kinds of ideas. (Remember the old slogan, “if men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament”?) What would it look like to really have more than two parties, “representation” not only of colors and classes now rarely seen, but representation of cross-cutting ideas and alliances? Every faculty I have ever been on that worked well had those cross-cutting issue-specific alliances in order to make agreements. There are Black, LatinX and Asian-American police officers where I live (Los Angeles). This was hard fought but also motivated by some who wanted to reform from within and others who wanted to see equal protection and safety for their communities—as well as “representation” at the table. As one of my intellectual mentors once said when asked how it felt to be chosen for some high levels jobs “because she was a woman,” she tartly answered it was, “better than not being chosen because I am woman!” (Thank you Barbara Babcock). To be at the table means to have some chance to influence decision making at that table, if representation is really diverse (in ideas as well as hues).

| How about “US Problem Solving Day”? |

5. How about “US Problem Solving Day”? Rather than naming another holiday for a leader, fallen or otherwise, why don’t we take a day out (and not just go shopping) where everyone would have to spend a few hours, in a group (or alone for those all American individualists), and think about how to solve some problem (big or small), like climate change, access to computers, food distribution, just plain “getting along” with differences?

| Words derive their meaning from contexts, history and usage. All of us now have a responsibility to listen to the words and phrases and slogans we use. We must ask ourselves, what words can we remake to help us remake ourselves? We don’t have much time, if the virus or climate change doesn’t get us, we will surely get ourselves. |

In these troubled times it might help to remember, from my field, as a lawyer, that our Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were born with original sin—slavery and inequality for many. Thurgood Marshall, Supreme Court justice, refused to celebrate the bi-centennial and I agreed with that then. The “We” in the people was small then, just a fraction of the population, but it is my secular religion, and my commitment to our work in conflict resolution, that “we” have and can continue to expand that word. “We” is a lot more of us than it was in 1776 or 1787 and the aspirations written in those documents (along with sinful parts, legitimating slavery and in the words of Abigail Adams, “not remembering the ladies”) are not yet fully realized. Consider how the musical Hamilton cleverly “flipped” the meanings and resonances of our founding days by changing colors of the participants, cadences of the music, and meanings of the words (irony, anyone? to achieve better meanings). I am not a Constitutional “textualist.” Words derive their meaning from contexts, history and usage. Young people create memes, we mediators “reframe” words of conflict to search for common ground, political strategists (full disclosure: my husband is one) craft slogans and taglines; lawyers create new ones (“corporation” and “union” anyone?) and all of us now have a responsibility to listen to the words and phrases and slogans we use. We must ask ourselves, what words can we remake to help us remake ourselves? We don’t have much time, if the virus or climate change doesn’t get us, we will surely get ourselves.

[1] Distinguished Professor of Law (and Political Science), University of California Irvine.

[2] Originally said by Rodney King, Los Angeles, 1992, see Carrie Menkel-Meadow, “Why We Can’t Just “All Get Along,”: Dysfunction in the Polity and Conflict Resolution and What We Might Do About It,” 2018. J. Disp. Resol. 5-25.

[3] Carrie Menkel-Meadow, “Remembrance of Things Past? The Relationship of Past To Future in Pursuing Justice in Mediation,” 5 Cardozo J. of Conflict Res. 97-115 (2004).