Universities Need to Do Better

by Heidi Burgess

January 31, 2022

| Guy Burgess and I are participating in Project Seshat, a highly interdisciplinary project examining how experts from many different fields from conflict resolution, to security, to law, to business (and others) think about and potentially respond to "hybrid" or "gray-zone" warfare. My working group (which included Michelle LeBaron, Peter Adler, and Scott McGregor in addition to myself), were asked to write essays reflecting on how our educational training, our professional careers, and our personal lives shaped how we viewed a particular "case"--a case entitled "State Devolution" which focused on Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan. The essays that the four of us wrote are all substantially broader than these original three questions, and they relate directly to areas of interest covered by BI, and our Constructive Conflict Initiative. For that reason, I asked Peter and Michelle for permission to publish their pieces here, and I am adding mine here as well. Scott's will be following a bit later. |

My original training looked at conflict systems as complicated systems, using that term in the way Wendell Jones taught us systems theorists do. According to Wendell, complicated systems have lots of parts, but they are all connected in known ways, and a change in one will bring about predictable changes in other parts of the system. Complex systems, on the other hand, have many parts, but they, themselves, are not all known, and their relationships are both not known, and also not predictable. As a result, complex systems cannot be modeled or modified in the same way a complicated system can be.

| In grad school we confused complicated and complex systems. We studied the social system (a very complex system) as if it were a complicated system which could be analyzed empirically to predict future conditions. |

In grad school, we tried to model the social system (a very complex system) using empirical techniques. So, I’d look at these cases, along with a number of other ones probably, to determine what I thought to be relevant variables. Then I would run statistical tests, such as multiple regression, to “figure out what was going on” and why.

The aim was to understand why conflicts happened much more than to figure out what to do about them. (In fact, much later, when I was teaching in a department of communications at the R1 University of Colorado (they made a big deal about being R1), anything that was “applied,” that was “practical,” was seen as “below them.” They were into theory for theory’s sake, and I’m sure the mores around the sociology department I got my degree from were the same, though I never remember that being explicitly stated.

What would the “key elements” have been? Likely government type, socio-economic data, identity group data (tribal, religious, ethnic, etc.), a measure of power of each group (primarily looking at the ability to wield coercive power, although feminist notions of power with and power to were beginning to be suggested as relevant, external actors and the nature of their interventions…likely more. All of these would (ideally) be represented by numbers, which would then be crunched to determine “the truth” about why each of these catastrophes was happening.

| Applied or practical research is not "below" what should be happening at an R1 university, as I was told. Rather, it is above what people were doing at my institution. They didn't know how to do research that mattered. |

How would my training have changed if it was what it should have been? Two factors are most important. First is I should have been taught about the different nature of systems, and how complex systems cannot be managed or even studied in the same way complicated systems should be. Second, there should have been an additional focus on application—once we had the theories, what did they imply about socio-economic and political change, and how might those changes be accomplished? This kind of thinking was not below us—it would be more accurately stated that it was above us. We didn’t have a clue about how to do it. (I should note that Kenneth Boulding published his seminal article “The Skeleton of Science” in 1956, so that was way before I was in graduate school. Boulding was at the University of Colorado. They should have noticed that article. But they didn’t. Boulding was an economist, so he wasn’t thought to be relevant to sociology. Had they noticed that article, they might have started teaching more appropriately about different levels of systems. But they didn’t.

| Universities should really encourage and support multi-disciplinary work, not just pay lip service to it. For a start, it should count towards tenure--maybe even extra! |

That suggests a third change that should have been made. They should have really encouraged multi-disciplinary work, not just paid lip service to it. When I was in grad school and later running the Conflict Information Consortium at the University of Colorado (yes, Guy and I stayed at CU despite all its problems after getting our BAs and Ph.Ds. there because Boulder was just too nice a place to live), the University said it encouraged multidisciplinary work. However, if you published an article with someone from another discipline, and it got published in an economics journal when you were in the Department of Sociology, it wouldn’t count towards tenure. If you joined a multi-disciplinary organization (such as the Conflict Information Consortium) and worked on some of our multi-disciplinary projects, that not only didn’t count for tenure; it would even be seen as detracting from one’s chances. So the only people we got to participate were tenured faculty (ideally, full faculty because participating with us harmed chances for promotion too) or faculty not on the tenure track at all.

| "Solving" intractable conflicts maybe a bridge too far, but making them more constructive is not. |

How does my life experience (as opposed to my professional experience) influence these views? My personal life and professional life are so intertwined that making that distinction is difficult, and probably not very meaningful. The only thing I’d add is to emphasize practicality. I want to know how to solve problems. Or, putting it more accurately, since I have spent my entire career studying intractable conflicts, I want to know how to change those conflicts for the better. (“Solve,” like “resolve,” is too strong a word, too high a bar.) But making conflicts more constructive is not. I want to know how to diminish U.S. polarization—and I want to be able to play a meaningful part in that effort (without having any illusion that I can do that alone—I need to be part of a cast of millions.) So both from a personal and professional point of view, I’d focus on practicality.

| You need to understand theory to be flexible and adaptable—to understand why things have gone off the rails when they do, and which of the various response options might be best suited to the situation. |

I was thinking, as I wrote this, that maybe I got the wrong degree. Master’s programs are said to be more practical, while Ph.D. programs are said to be more theoretical. Now I have taught in two masters programs that were highly theoretical, so that isn’t always the case. But I’m thinking that that distinction isn’t a good one anyway. Both kinds of programs need to be both. The problem with practical master’s programs is they often teach students to follow cookbooks. They learn skills but have little understanding of which skills to use when, why, and what to do when things don’t go according to the script. You need to understand theory to be flexible and adaptable—to understand why things have gone off the rails when they do, and which of the various response options might be best suited to the situation.

I also think that both Masters and Ph.D. programs should look at problems—systems—more broadly. This relates in part to the multi-disciplinary issue raised above, but it is more than that. Whenever I suggested an idea for a paper for a course, or for my dissertation, I always started out very broad. I was always told to narrow my focus—narrower and narrower, so that I could clearly measure my little, tiny dependent variable and the three or four (maybe even ten) independent variables that might be influential. Such inquiries never managed to see the whole system or understand the dynamics that drove it.

| Intractable conflicts cannot be solved by one mediator galloping in on a white horse to save the day. It is going to take massive numbers of people working on different aspects of the system over multiple years—what we originally called “Massively Parallel Peacebuilding” which we are broadening now even more to “massively parallel problem solving.” |

As a more current example, I recently got done reading Peter Coleman’s book on U.S. polarization entitled The Way Out. Peter does much better than most in writing about systems and complexity, yet the research he uses to back up his claims are all narrowly focused little experiments, often carried out in psychology labs with undergraduate students pretending to be in situations in which they aren’t. The assumption is made that this accurately reflects real people making real decisions in complex situations. I’m skeptical to say the least!

That’s why Guy and I started the Conflict Information Consortium and Beyond Intractability—we wanted to develop as broad an image as possible about what drove intractable conflicts and what can be done to manage them. We don ‘t believe that these conflicts can be solved by one mediator galloping in on a white horse to save the day. It is going to take massive numbers of people working on different aspects of the system over multiple years—we originally called this “Massively Parallel Peacebuilding” which we are broadening now even more to “massively parallel problem solving.” Others have come up with similar ideas—John McDonald and Louise Diamond with “Multi-Track Diplomacy,” Bill Ury with his ten “Third Side Roles.” But neither of these ideas, and certainly not ours, have caught on much, because no one likes thinking big and complex. The human brain is much more suited to small and simple. Educational programs, rather than encouraging such thinking should, instead, be encouraging as broad thinking and investigating as possible.

I’d like to add a couple more things after meeting with my group. First is agreeing with Peter Adler’s observation (shared in detail in his response turned BI blog post) that the elements evident in Case 7 on State Collapse are typical of lower-level intractable conflicts as well. Peter talked about water wars in Oregon and California’s Klamath Basin, which have been going on for decades, and also the hyper-polarization we are witnessing throughout the U.S. at all levels of social organization from Congress to families.

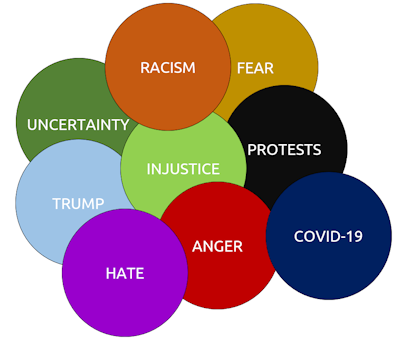

All these conflicts, Peter observed, have state and non-state actors, sabotage, ideological subversion, and right-wing (he said—I’d ask left-wing too?) extremist behavior. They also, I would observe, share characteristics of complex intractable conflicts or wicked problems. No one knows accurately what is going on, and what is going on is constantly changing. The actors are changing, and their relationships are constantly changing. The environment is changing. There are high levels of misinformation, distrust, fear, even hatred. There is no way to know for sure what interventions might work to defuse the situation, and which might make it worse (although we can make educated guesses).

| It is essential that the conflict resolution community, working in concert with lots of other professional communities, begin focusing intently on de-escalating hyper-polarization in the U.S. and in other developed democracies, as we are already in at least a gray-zone civil war, with the possibility of a kinetic civil war on the near horizon. |

As Guy Burgess, Sanda Kaufman, and I are arguing in an article to come out in the summer issue of the Conflict Resolution Quarterly, (and online sooner, we hope) it is essential that the conflict resolution community, working in concert with lots of other professional communities (such as those represented by the SESHAT group), begin focusing intently on de-escalating hyper-polarization in the U.S. and in other developed democracies.

If “hybrid-warfare” is soft warfare (we discussed in our group that no definition was ever decided upon)—using strategies such as social media manipulation, election tampering (I’m not agreeing with Trump that 2020 was illegitimate, but I am arguing that what is going on now in advance of the 2022 midterms is illegitimate and dangerous), disinformation campaigns, efforts to undermine effective governance—the U.S. is clearly already embroiled in a hybrid civil war. It could easily transform into a kinetic civil war. And even if it does not, scholars of hybrid warfare understand that the damage that hybrid or gray-zone warfare can unleash is as great (or perhaps, eve greater) than kinetic war. So it is high time, in Guy’s and my view, that anyone and everyone who has any notion about how to de-escalate such fraught situations and help build peace should start focusing their efforts on doing so.