The "Two Taproot (or Fuses) Theory" of Social Unrest

By Heidi Burgess and Guy Burgess

July 7, 2020

In 1999, the Conflict Information Consortium partnered with Conflict Management Initiatives to undertake The Civil Rights Oral History Project, during which we interviewed 19 Community Relations Service (CRS) mediators about how they mediated racial conflicts. CRS is part of the U.S. Department of Justice, formed as part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. They were present—and helped de-escalate and resolve—most (maybe all) of the high-profile racial conflicts in the U.S. (including, among many others, the aftermath of Martin Luther King's assassination, the Rodney King riots in LA, Wounded Knee, church arsons, James Byrd's murder, Trayvon Martin's murder) as well as hundreds of lower-profile cases.

One of the mediators we interviewed was Silke Hansen, who worked out of the Denver office, but was one of the mediators who worked the Rodney King riots. She told us about "Gil Pompa's two-taproot theory of social unrest" which is highly relevent to the events of 2020. [1]

I heard this from Gil Pompa [a former director of CRS], so I refer to it as ‘Gil Pompa's theory.’ In essence, he said that in racial conflicts, there are two taproots growing simultaneously. One is a perception or belief of unfair treatment or discrimination. The other is a lack of confidence in any redress system. There is the belief that, "Even if I complain, it is not going to make a difference." And those two beliefs (or taproots) are growing in force, side-by-side.

Then there is a triggering incident. Rodney King was a classic example. And that triggering incident then results in these roots really exploding. Now, the reason that I said I have changed it slightly is because I can't really see roots exploding. So I have changed it to say that there are two fuses leading to a bomb, and those two fuses are constantly strengthening and growing in intensity.

But even though these two fuses leading to the bomb are there and are becoming more dangerous, it's not until that triggering incident that the bomb explodes and you have violence. If you could have disconnected or defused either of those fuses, the triggering incident wouldn't have done anything.

If people who feel they are facing despair had an effective redress system, you wouldn't get that tension. If you didn't have a perception of disparity in the first place, you wouldn't need that redress system. But with both of those growing in intensity, that triggering incident--and it could be almost anything--will then set it off.

And then once you have that triggering incident, I think one of the mistakes that we often make in responding to that is that all we look at the triggering incident. We try to resolve the triggering incident, and we totally miss all of the pieces of those two fuses. We don't even look at those fuses! But the fuses are still there, so unless they are dealt with, they are going to regroup after a while, even when people don't even remember the triggering incident anymore.

So part of our job, if you are really trying to deal with and respond to a violent conflict, is to recognize what those two fuses look like. Because if you can't deal with them, another triggering incident is going to set them off again.

With the Rodney King situation, if you remember the disturbances or "civil disobedience" or "riots" or "revolution"—the semantics of what you called it became a very big issue—those events occurred not when Rodney King was beaten, even though you would think that the beating would have generated anger. But rather, the incidents occurred when the redress system didn't work. When the police officers were found "not guilty," that is when all hell broke loose.

The anger was about much more than the Rodney King incident; it was about these two fuses that had been growing. Rodney King was just a triggering incident that set that off. And you can look at other examples of that as well. But it's an illustration which makes sense, even when you present it to institutional heads; they understand the importance of addressing perceptions of inequality. Even if they think they are doing everything fairly, they realize that it is in their best interests to not have those fuses growing in their community.

So I say, [when I’m talking to police chiefs about my helping them respond to a triggering event] "Maybe what is needed here isn't labeling you as racist. Maybe what's needed is for you to have a better opportunity to explain to the community what you are doing. Maybe the community just doesn't understand all of the positive things. I can help you with that, too."

But, having the illustration of the fuses is a good way to help people understand some of the dynamics of a community.

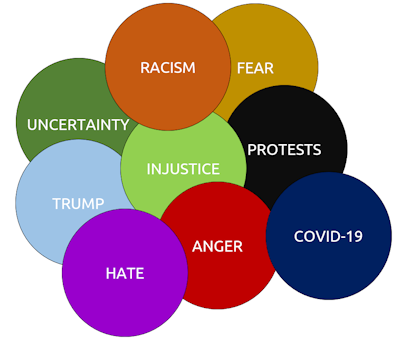

Applying this theory to the George Floyd events makes a great deal of sense. Clearly both of these taproots/fuses had been growing for a long time. In fact, the entire history of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation has been littered with terrible crimes for which there was no effective remedy. Blacks were set up to fail, and have remained structurally discriminated against ever since. Further, Blacks and other minorities have little recourse when they are wronged. The American judicial system is such that police are very seldom held responsible for abusing blacks or other people of color. Private citizens, too, at times, have not been charged or have been aquitted for racially-motivated crimes. That history, and the fact that these kinds of incidents happen very often (several have already happened in the one month after Floyd was killed) gave Blacks in Minneapolis, and indeed, people of all colors all over the country and all over the world, the sense that there is no recourse, no means of redress.

| It is important to keep these taproots/fuses in mind, both when protesting, and when responding to the protests. The inequities between the races need to be remedied, and there must be meaningful redress when problems occur. |

It is important to keep these taproots/fuses in mind, both when protesting, and when responding to the protests. The calls to "defund the police" only address the triggering incident—if they do that. They do not address either of the taproots/fuses. So even without police (and indeed, perhaps more likely without police) there will be many other triggering incidents. The only way racial conflict is going to be reduced or resolved is by addressing both of the taproots/fuses. The inequities between the races need to be remedied, and there must be meaningful redress when problems occur. While some people are beginning to talk about such changes, there isn't enough effort going into those areas of policy yet. There needs to be much more.

[1] Interview with Silke Hansen, former Community Relations Service Mediator, Denver Office of CRS. August 3, 1999. Part of The Civil Rights Mediation Oral History Project.. https://www.civilrightsmediation.org/interviews/Silke_Hansen.shtml

Matagraphic: Two taproots: Wikimedia: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/43/Dicotyledoneae_Asteraceae_herb_-_root_system%2C_primary_root_becomes_tap_root_and_lateral_roots.JPG RoRo/CC0; Bomb: https://pixabay.com/vectors/bomb-cartoon-iconic-2025548/ Free for commercial use, no attribution required.