Reversing Polarization and Escalation - Part 1

by Heidi Burgess

November 19, 2021

I have been in the process of writing Section 4 of our coming Constructive Conflict Guide, which is focused on things "good-faith actors" can do to de-polarize and de-escalate intractable conflicts both at the interpersonal and at the societal level. Since this material isn't going to be published until the rest of the Constructive Conflict Guide is complete, I thought I'd start sharing excerpts of this material in the Newsletter and on the Constructive Conflict Blog in the interim. The first part of Section 4 deals with de-escalating destructive, "us-versus-them" confrontations. My previous post focused on defeating "us-versus-them" narratives; today I want to focus on de-escalation of the conflicts that result from those narratives.

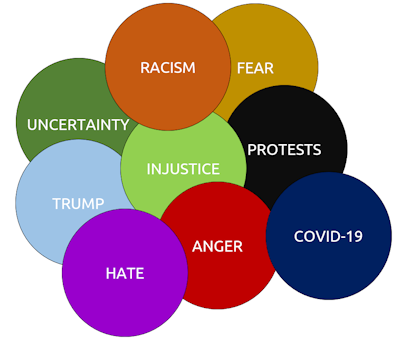

I should start out by noting that escalation is actually driven by much more than us-versus-them narratives, although that is an important beginning. The full Constructive Conflict Guide will include a chart that shows (and explains) the many different elements that all interact to drive escalation and polarization higher and higher. If you look at that chart, you will see it includes over twenty different processes, each of which amplifies several of the others in a reinforcing (positive) feedback loop. It is very easy to feed this "beast," pushing escalation ever higher. It is much harder and slower to reverse those trends. BUT, it is possible to do.

| Many things drive escalation, but there are also many things we can do to slow and ultimately reverse those processes. Once we understand the many ways in which escalation can trap us, we can avoid those traps or climb out of them if we have fallen in. |

The good news hidden in the chart, is that there are so many things that drive escalation, there are also many things we can do to slow and ultimately reverse those processes. Once we understand the many ways in which escalation can trap us, we can avoid those traps. If we discover that we have already fallen into a trap, we can work to climb out. In addition, there are many things we can do to help our communities resist destructive escalation while, at the same time, more constructively addressing important issues that are at the core of most conflicts. Although the common assumption seems to be that there is little, if anything, that individuals, groups, or communities can do to avoid or reverse polarization and escalation, there are actually so many things that it is going to take not one, but two blog posts to cover them all!

Escalation Awareness

| The first critical step toward de-escalating conflicts is building awareness among disputants about how very insidious and dangerous unbridled escalation is. |

The first critical step toward de-escalating conflicts is building awareness among disputants about how very insidious and dangerous unbridled escalation is. When people are drawn into its downward spiral, they do not understand that their images of the other side are distorted. They do not understand that their own actions are likely contributing to the problem and making the other side respond as it is doing. If disputants can be shown how their own actions are driving the other side to respond as they are; if they can come to realize that at least most of the people on the other side are not as bad as they think (that's not including the bad faith actors, who maybe are that bad), they (good-faith actors) are more likely to be willing to change their own behavior, particularly once they realize that they are making escalation and polarization worse.

Tactical Escalation

Sometimes disputants (particularly low-power disputants) try to escalate a conflict intentionally because the other side does not care about an issue as much as the lower-power party does, and the lower power party thinks that by escalating the conflict they can get the other side's attention, or even get them to agree to make desired changes. Sometimes this is true, and it works, as Louis Kriesberg explains in his essay entitled Constructive Escalation.

| Sometimes tactical escalation works, but it can quickly get out of control and has a habit of strengthening one's enemies as much or even more than it strengthens one's friends. |

But this is a dangerous tactic, not only because escalation can quickly get out of control (as we discussed above), but also because it has a tendency to strengthen one's enemies as much as, or more, than it strengthens one's friends. So, for example, the Left held huge marches around the world in the summer of 2020, protesting the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This drew a great deal of attention to the problem of police violence, which was good. However, in addition to almost universally-supported calls for strong and effective measures to prevent and punish police misconduct, there were also widespread calls to "defund the police." This implied to many that the advocates of this policy believed that all policing was oppressive or otherwise harmful, and should be eliminated entirely. However, it turns out, most U.S. Blacks, who are victims of widespread community violence, generally are against defunding the police. Rather, they want the police in their neighborhoods because they feel that police are doing more to prevent crime than to cause it. So not much defunding of police has happened and where it did happen, the funds were soon restored.

But, the campaign has been a huge rallying cry for the Right, which has been able to successfully use it to paint Democrats as "anti-police" and "pro-crime." William Saletan writing in Slate asserts that argument was a key reason that the Democrats lost many Senate seats in November of 2020. So in that case, escalation worked to strengthen the opposite side more than it worked to strengthen the party that was demonstrating.

For these reasons, tactical escalation efforts designed to promote awareness of a problem and efforts to solve it should be undertaken very carefully, and only if it is deemed the only way to gain the attention of the other side and the larger community. Parties using tactical escalation should also engage in other de-escalating behaviors and de-escalatory language simultaneously, so as to give the other side an opportunity to respond collaboratively, instead of hostilely. Ways of doing this are suggested below.

Constructive Confrontation

One alternative to intentional (tactical) conflict escalation is what we call "constructive confrontation." This process has four steps.

| Constructive confrontation enables disputants to confront a conflict without escalating it. The steps are: assessing the conflict's true complexity, setting goals and creating a collaborative image of the future, and then using an optimal power-strategy mix (meaning integrative and exchange power more than coercive power) to bring that future about. |

- First is carefully assessing or mapping the conflict to enable you to "see the complexity" and understand, as much as possible, what is really going on.

- Second is setting your goals. Rather than seeking total victory, which is likely to be a recipe for continued destructive conflict, conflicts can be de-escalated by setting goals that allow the other side to meet as many of their interests and needs as possible too.

- A closely-linked step is developing a collaborative image of the future. If you can develop an image of the future in which everyone would want to live, that is going to be much more successful than seeking an outcome that is completely unacceptable to the other side.

- The fourth step in constructive confrontation is considering response options which can be interest-based (focused on the negotiation of mutual interests), needs based (focusing on meeting unmet human needs through problem-solving workshops and related processes), or rights based (focused on adjudicating rights). If the conflict cannot be resolved or transformed by these actions, the next option is to utilize power. But that doesn't necessarily mean using coercive power (force). Rather, it means using a mix of power strategies, carefully designed to minimize coercion as much as possible, by using a combination of integrative and exchange power with as little coercion as possible to reach what we call the "optimal power strategy mix."

Gandhian "Step-Wise" Conflict Escalation

| Gandhi used self-limiting conflict processes that had built in devices that kept the conflict within acceptable bounds. He also maintained personal relationships with his opponents and sought truth and justice, not victory of one side over the other. |

Another way to get the other side to notice a conflict and get them to take your interests and needs seriously is to copy the way Gandhi designed his pressure campaigns. Gandhi used self-limiting conflict processes that had built in devices that kept the conflict within acceptable bounds. For instance, he always escalated conflicts in a step-wise fashion, interrupting pressure campaigns with withdrawal, periods of reflection, evaluation, and repeated attempts to negotiate an acceptable outcome. If those efforts failed, he would escalate again, but then pull back, and repeat the reflection, evaluation, and negotiation processes.

Gandhi also stressed the importance of maintaining personal relationships with the opponents, and, as Fisher and Ury later urged, "separating the people from the problem.." He also eschewed secrecy, insisting on the open flow of information, including the sharing of his movement's plans for upcoming actions. Lastly, Gandhi's theory of "satyagraha" (the force of truth) saw the goal of conflict being persuasion and the discovery of truth, not coercion. This shifted the framing of the conflict away from a win-lose frame to a win-win frame. Gandhi's escalating commitment was not to winning, but to the discovery of the truth of social justice--even if that discovery determined that the opponents' views were in part, or even completely, correct. Truth and justice for all were the goals, not victory of one side over the other.

Avoid the "Sacrifice Trap"

| It is important to provide people with a "face-saving" way of escaping bad decisions. It is far better to sympathize with and support those honest enough to admit they've made mistakes, than it is to shame them for changing their minds. |

It is also important to prevent the "Sacrifice Trap" (discussed briefly, above, in the description of the escalation diagram) from locking people into a continuing, destructive course of action. People often get caught in this trap because they have a tendency to escalate their commitment to a previously chosen, though failing, course of action in order to justify or 'make good on' prior investments. ("We can't give up now--we've invested too much!")

While this is a problem when it is the individual making decisions on their own behalf, it is an even bigger problem when leaders ask their constituents or followers to make huge sacrifices—even of their life—so the leader doesn't have to admit that their cause was lost, unwise, or, at least, unwinnable. While there is much evidence that shows that conflict behavior is not rational; it is largely driven by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, still, if people can see how much a conflict is hurting them, and how little chance they stand of improving their situation if they continue to fight, it might help facilitate de-escalation. (This is a necessary condition for what William Zartman calls "ripeness." ) All of this suggests that it is important to provide people with a "face-saving" way of escaping bad decisions. It is far better to sympathize with and support those honest enough to admit they've made mistakes, than it is to shame them by accusing them of "flip-flopping," which is a taken to be a sign of weakness and untrustworthiness in American politics.

Pick Your Fights

| The time, energy, and resources we each have available to participate in civic debate is limited. We, therefore, ought to concentrate our efforts on places where we can really help make things better and not get caught up in the amplification of destructive escalation spirals where we are only making things worse. |

Let things go when you can. Not every provocation needs to be responded to in kind. If the issue isn't important to you, don't turn it into a tit-for-tat driver of escalation Ignore it; oftentimes it will just go away. And if it doesn't, try cooperation, or simple listening, first. As we will point out in Part 4B, sometimes having someone empathically listen is enough to get people to calm down a lot. It might not resolve the entire conflict, but it often changes the tone, and the willingness of the other side to listen to your views and negotiate a mutually-acceptable outcome.

It is also important to remember that the time, energy, and resources we each have available to participate in civic debate is limited. We, therefore, ought to concentrate our efforts on places where we can really help make things better and not get caught up in the amplification of destructive escalation spirals where we are only making things worse (something that is all too easy to do on social media).

Reframing the Problem

As I said above, it is very helpful to reframe the problem so that you no longer define the problem as being the other side, but rather the destructive conflict dynamics, such as escalation and polarization, that are causing you and people on the other side to behave in ways that are preventing problem-solving, rather than enhancing it. Once you define the problem as conflict escalation (or "hyper-polarization" as it is being called with respect to U.S. politics these days), then you realize that there are much more effective strategies for solving the problem than just pushing harder and harder against the other side. It even suggests that collaborating with the other side to change conflict interaction patterns and to push back against bad-faith actors who intentionally drive escalation is helpful. Increasing numbers of scholars and pundits seem to be making such arguments now (in late 2021), one example being Peter Coleman, in his new book The Way Out.

Stop Blaming the Other

| Reframe the problem: the problem is not the other, but rather destructive conflict dynamics that are created at least in part by oneself as well as the other. So we all have to work together to change those dynamics and start addressing the real conflict problems effectively. |

A closely-related way to reframe the problem is to stop framing the problem as created by "the other," and acknowledging that the problem is likely created, to varying degrees, by everyone, including oneself. Typically, in intractable conflicts, people on all sides assert (and believe) that the other side is evil, greedy, stupid, or wrong, and that they, themselves, are right, good, and generous. Even if that is true, it seldom helps resolve the conflict—it just leads to an escalating conflict spiral. A better approach is that suggested by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen, in their book Difficult Conversations. They make the distinction between "blame" and "contribution," where blame judges the other side and looks backwards. Contribution looks for understanding of how everyone contributed to creating the present situation. It goes both backwards to see how the situation got to be and forward to figure out how to fix it. Focusing on contribution thus enables learning and problem solving, while focusing on blame causes conflicts to become more escalated and intractable.

Use De-escalatory Language

I-statements: We will talk about this more in Part 4B, but the basic idea is to try hard to use language that calms things down, and gets one listened to, not written off or responded to hostilely. One commonly taught way to do this is to use "I-statements," not "You-statements. I statements usually start with "I feel" or I felt" rather than "you did." So, instead of saying someone else did something wrong ("You ignored me!"), say how you are impacted: "I felt confused and disappointed when I wasn't able to reach you in time for us to meet."

Or, as another example, instead of calling for "defunding the police," (which implies that the all police are doing something wrong), one might use an I-message to explain one's thoughts in more detail. Such as" "I am very concerned about police excessive use of force. I think that we need to examine how police are responding to different kinds of calls, so we can figure out what we can do to make them more effective and sensitive to community needs. Perhaps some types of calls would be better handled by other kinds of people--for instance social workers or therapists, rather than police? It would also be useful to hear from police officers about how they view this problem, about the pressures that they face, and about reforms that they think would help them better serve the community." This, as I understand it, is really what "defund the police" really means to many people (perhaps without the last sentence suggesting it would be useful to listen to the police themselves). So why not say it that way, which is a position to which many more people are likely to agree?

| Listening empathically does not mean you have to agree with what the other person is saying. It just means listening carefully and then showing you heard and understood what the other person was saying, and that you care about their thoughts and feelings. That can go a long way toward de-escalating a tense situation, and might even get them to listen to—and really hear—you. |

Empathic Listening: As we discussed above, listening is a powerful alternative to knee-jerk escalation. As we will explain in more detail in an upcoming post, listening empathically does not mean you have to agree with what the other person is saying. It just means you have to show them that you heard them and properly understood what they were saying. Often, one of the main grievances of lower-party people is that they believe that no one is listening to them or cares about what they have to say. Empathic listening shows that you have heard them, and you DO care what they have to say. That can go a long way toward de-escalating a tense situation, and might even get them to listen to—and really hear—you.

And There is More!

When Guy and I first started talking about this project, I lamented that we had an excellent handle on the problem, but didn't have many ideas about solutions. But as I began thinking about it, I realized how wrong that statement was! The items above are only half of the list we came up with. I'll share the rest of the list in the next blog post.